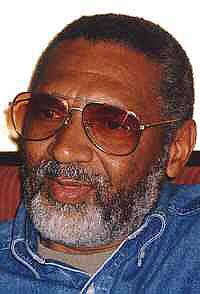

The pt. 7 contributor to our dialogue with black jazz writers on their respective career arcs, issues they’ve faced, and their various observations on recent recordings is MARTIN JOHNSON, shown (left) in the photo below conversing with the late, great soprano saxophone master Steve Lacy.

Martin Johnson got his start writing about jazz for the Amsterdam News in 1984 — joining previous contributors to this series Ron Scott and Herb Boyd (scroll down or check past installments below) as vets of that long-running cornerstone of the black dispatch. Within a year Martin was writing regularly for Newsday and The City Sun. After diversifying into pop music and film, he wrote for a wide variety of publications and websites, including Essence, Vogue, Elle, the Village Voice, the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Chicago Tribune, the NY Sun, Los Angeles New Times, the SF Weekly, Rolling Stone, Vibe, Tower Records Pulse!, Downbeat, JazzTimes, Paste, amazon.com, bn.com, and numerous other outlets.

Earlier this decade, as music journalism retreated from a primary revenue source into a sidelight income, Martin began writing critical analysis of sports for the NY Sun, and he launched an information service called The Joy of Cheese, conducting public and private tastings in New York City. He presently writes about music for the Wall Street Journal and New York magazine, and on sports and many other cultural matters (including music) for www.theroot.com.

What orignially motivated you to write about serious music?

I loved to write and I loved music. In the third grade, my Dad encouraged me to write a book report on Milestones, which I had always enjoyed mostly because I had the same type of shirt Miles Davis wore on the cover. I was especially thrilled that the album included "Billy Boy", a song I knew, but I was really blown away by the catchy rhythms of "Straight No Chaser." I had a blast writing about the record and thereafter whenever I could turn a school assignment into writing about music I did.

I worked at WKCR-FM in college [Columbia U] both as Jazz Director and as a member of the Executive Board. My senior year I co-produced the "Interpretations of Monk" concert. I had won journalism awards in high school so this seemed like a natural synthesis. After graduating I spent a couple of years spinning my wheels in an unproductive job, so I quit, took unemployment, and marched into the office of the Amsterdam News and told Mel Tapley that I would write about jazz for him. Fortunately he interpreted my declaration as a request and said "sure young man, what would you like to write about?"

When you began writing about jazz were you aware of the dearth of African Americans writing about serious music?

No, I went through a difficult adolescence as my family moved from Chicago (Hyde Park/Kenwood no less) to Dallas right before I entered ninth grade. In school I was frequently called an Uncle Tom and beaten by other African Americans because (1) I lived in the white neighborhood. (2) I was the new kid. (3) I didn’t speak with a "black" accent and (4) my musial tastes were "white." (I think today my tastes would be called eclectic: I liked all the things that my black classmates liked – WAR, Isley Brothers, P-Funk… but I also liked Steely Dan, Bob Dylan, and Joni Mitchell and — gasp — Miles Davis, Duke, Coltrane, etc.

I figured getting waaaaaay away from there to go to college would solve this situation, but I was wrong. When I was Jazz Director at WKCR I was called on the carpet by the Black Students Organization and asked to explain why the station didn’t play any black music. I enthustiastically explained about the annual day-long festivals devoted to Thelonious Monk, Billie Holiday, Duke Ellington, and Coleman Hawkins among others, and that the station was presently doing a 200 hour plus marathon devoted to the music of Max Roach. I remember the woman bellowing at me "no, I mean real black music!" By that time I was accustomed to the fact that my personal concept of blackness might not match other African Americans’ concept of blackness and I could mostly deal with that. But if I had to defend the blackness — er, the "real" blackness — of Billie, Duke, Monk, and Bean, then I knew I was in with people that I shouldn’t be in with and I left.

So I started writing and one of the first people I meet is Don Palmer, another African American writer with, ahem, eclectic tastes. Then I meet Greg Tate, then Stanley Crouch… I didn’t know if these cats had written about Miles Davis in the third grade, but it felt like they had. I was thrilled and proud to be part of this contingent; I felt like I’d found the crowd I’d been looking for all my life.

On the other hand, from the way that musicians treated me, after a while I soon realized that my colleagues might not be the norm. All jazz musicians in general, but African American musicians in particular, went out of their way to look out for me; sometimes they’d come to my home for interviews. They’d call me to praise the pieces I wrote. I wasn’t getting paid much money for my work, but it was richly rewarding.

Why do you suppose that’s still such a glaring disparity — where you have a significant number of black musicians making serious music but so few black jazz media commentators?

With the skills that it takes to be a great cultural commentator, you could do a lot of things that would make a lot more money. I assume that most African Americans with the option choose not to starve and worry endlessly about the rent.

[Editor’s note: Hmmm… the same could be said regarding musicians who choose the jazz path rather than the path more clearly paved with potential gold; proving once again that there is something about our respective quests that transcends the traditional strive for creature comforts.]

Do you think that disparity, or dearth of African American writers contributes to how the music is covered?

Sure, but that’s one of the breaks of the game.

Since you’ve been writing about serious music, have you ever found yourself questioning why some musicians may be elevated over others and is it your sense that has anything to do with the general lack of cultural diversity among the writers covering this music?

No, not really. At the level I work at, so much of this stuff is just timing and luck. If I wrote for music magazines with some regularity, I might be focused to wonder.

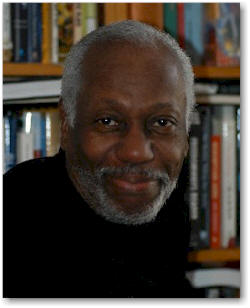

Martin Johnson with the inimitable Cecil Taylor

What’s your sense of the indifference of so many African American-oriented publications towards serious music, despite the fact that so many African American artists continue to create serious music?

In some ways I’m the wrong person to answer that question; remember I grew up amongst African Americans who thought that listening to Duke was "acting white."

[Editor’s note: …Which causes one to wonder aloud how many of our previous correspondents grew up in similar circumstances; I don’t recall there being such a phenomenon for those of us who grew up in the 50s and 60s — we may have been considered a bit musically different or even "odd" — back then the term was "off-beat" — but not "acting white."]

On the other hand, you sell more issues with Beyonce on the cover than with Cassandra Wilson. Overall, though, I think most African American publications dropped the ball on critical analysis of life… cultural and otherwise a long time ago, so it should come as no surprise that jazz falls through the cracks.

How would you react to the contention that the way and tone of how serious music is covered has something to do with who is writing about it?

I think that’s stating the obvious. Observations about any cultural work will vary from observer to observer.

In your experience writing about serious music what have been some of your most rewarding encounters?

Geez. I have been writing for 25 years. I could go on a while on this one. Hmmm. In 1985 I was invited to Max Roach’s house to watch a ball game. He was checking me out before agreeing to an interiew. Max tested me on my knowledge of Negro League stars. Satchel Paige? Of course! Josh Gibson? Hit a homerun out of Yankee Stadium! Oscar Charleston? Ummmm… Max leaned back on his sofa and smiled, looked at me and said "you don’t know as much as you think you know." That was true about baseball and is good advice in general. When I asked him about his insatiable appetite for experimentation, he offered another resonant piece of advice, "you can’t win today’s ballgames with yesterday’s home runs."

A few weeks later the phone rang one morning when I was sleeping late. I rushed to answer it (no voicemail in those days) and the man on the other end is Sonny Rollins, he heard I wanted to interview him. I thought I must have been dreaming. Rollins asked if he should call me later (are you kidding, how often is Sonny Rollins just going to ring me up!) I did the interview on the spot and he spoke at great length about everything.

I had two memorable encounters with Don Cherry. In the mid-80s he and Eagle Eye met me at the radio station and we walked the two miles down the Upper West Side to Gray’s Papaya so his son could get a hot dog, and then with the traffic whizzing by us on Broadawy, we sat on one of the benches in the parkway between the lanes on the busy street and did an interview. Then a few years later, I was to meet him in an East Village bar for an interview. He arrives on roller skates! He besieges the bartender to put on a CD he has. The bartender agrees; it’s Neneh’s debut disc and Don dances on his roller skates for Buffalo Stance before settling in for the interview.

Lunch with Betty Carter in 1992 ahead of the Vogue piece I wrote on her was great. For the first time in my life I had an expense account, a rather large one at that. But Carter insisted on going somewhere fairly modest. We ate at a Union Station area restaurant with outdoor seating and while we were talking Jimmy Heath walks up and the two of them trade great war stories about the 50s and 60s. Then afterward, we shop together at the Farmer’s Market and she wouldn’t even let me send her home in a limo, but she seemed genuinely flattered that I wanted to.

Walking through Tompkins Square Park in 1984 with Butch Morris was an education as to how he hears the world around him.

Lastly, and perhaps a surprise, sometime in the mid-90s Downbeat assigned me to do an equipment piece on Adam Holtzman. We met on Avenue A, got massive pastrami sandwiches at Katz’s Delicatessen, and then went to his studio, in a basement on the Lower East Side. Then for the next four hours he pulls out rig after rig and plays me lines, if not entire songs that he performed with Miles Davis and with Chaka Khan. It was like a private concert.

What obstacles have you run up against — besides difficult editors and indifferent publications — in your efforts at covering serious music?

Um, my editors have been great. All of them. Seriously. Okay, maybe one or two exceptions but in 25 years that means all of them. I got lucky. I got into the biz at a good time, made some great connections, lucked into a few others, never expected this stuff to be easy, and I’ve had a great time. It saddens me a little that you can’t make a living writing about this music, but you can’t make a living writing about sculpture either.

If you were pressed to list several musicians who may be somewhat bubbling under the surface or just about to break through as far as wider spread public consciousness, who might they be and why?

My list includes: Matana Roberts, Jenny Scheinman, Jonathan Blake, Tyshawn Sorey, Noah Preminger, Ted Poor, Loren Stillman, Michael Attias, Edward Ratliff, Lage Lund, David Binney, and many, many others.

What have been the most intriguing new records you’ve heard this year so far?

I’m still enthralled by Mike Reed’s 2008 releases. Okay 2009, Joshua Redman’s new one as well as those by Robert Glasper, Burnt SUgar, Melvin Gibbs, Darcy James Argue, Positive Catastrophe, Pedro Giraudo, The Tiptons, Vijay Iyer, Andrew Green, Klaang, Oran Etkin, John Herbert, Carl Maguire, Tim Kuhl, and 13th Assembly.

Next time: Bridget Arnwine