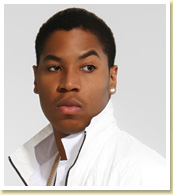

Our series of conversations with black music writers continues with a contribution from Robin D.G. Kelley, who is currently a Professor of American Studies & Ethnicity at the University of Southern California. The author of several books Robin’s forthcoming release Thelonious Monk: The Life and Times of an American Original (Free Press) is eagerly anticipated, set for October ’09 release. Additionally he is also completing Speaking in Tongues: Jazz and Modern Africa (Harvard University Press, set for 2010 release).

Robin D.G. Kelley has contributed to numerous newspapers and periodicals on jazz and other subjects, including the New York Times, Rolling Stone, Code Magazine, the Utne Reader, Black Music Journal, and Boston Review.

Robin D.G. Kelley

Our conversation began with the customary opener: What motivated you to write about serious music in the first place?

I grew up with the music. I was introduced to this music initially through my mother, who arranged for me to have trumpet lessons with Jimmy Owens when I was in the second grade (this was New York in 1969). As I got older, my tastes branched out, but I never lost a connection with the music because of my older sister, who also loved the music. But my love for this music was reborn after my mother married a jazz musician, who incidentally was white. By that time I was playing piano by ear and some bass but never really studied with anyone. Under his tutelege and thanks to my sister’s prodding, I got deeper into music then labeled avant-garde — Ornette Coleman, Cecil Taylor, Albert Ayler, etc., in addition to Mingus, Monk, Miles, etc.

When I got to college and decided that I wanted to become an historian, I considered writing about the music but was pulled more into politics and social movements. I did write (bad) poems about and inspired by these artists, but not much more until the early 1990s. I began playing more, reading more, and of course listening a great deal, but I also started writing about hip hop. That gave me the confidence to write about a variety of black musical forms. I never became a "critic" in the formal sense, but I began exploring broader social and historical questions pertaining to "jazz" in both my published essays and the classes I taught.

When you started on this writing quest were you aware of the dearth of African Americans writing about serious music?

When I began to read about this music — mainly for pleasure (whereas most readers choose fiction for their light reading, I had a jones for biographies of jazz musicians; most were terrible but that didn’t stop me from devouring them), I quickly learned that there were very few black writers in the field. I was fortunate in that one of the first books I read that left a huge impact on me was A.B. Spellman‘s Four Lives in the Bebop Business. It is a bona fide classic. I also wore out Arthur Taylor‘s Notes and Tones, read everything Baraka [editor’s note: see Ron Washington’s piece referencing Baraka’s new book Digging elsewhere in The Independent Ear] ever wrote on the music, from Blues People to Black Music, and learned a great deal from Stanley Crouch, whose insights on this music are often unmatched.

These were foundational texts that served as my model for writing, but quickly I discovered that they were the exception, not the rule. I was blessed to become friends with the late Marc Crawford, one of the unsung black critics of this music; he really inspired me and is responsible for my decision to undertake a book on Thelonious Monk. Things have changed a little but not much. There are a few out here, but so many of the so-called jazz critics seem to operate as an exclusive club. I don’t think it’s entirely racial; it’s partly generational, partly folks protecting their turf. And it’s not everyone. But as Monk would say, sometimes I feel a draft.

Why do you suppose it’s still such a glaring disparity — where you have a significant number of black musicians making serious music, but so few black media commentators?

Part of it has to do with the establishment; it’s hard to be a member of the club. On the other hand, I don’t think there is a whole lot of interest on the part of young black writers/scholars. I’ve taught courses on jazz and politics, the anthropology of jazz, and a seminar on Thelonious Monk, and the number of black students who take these courses or are interested is quite small. In fact, my biggest frustration with some of the African American students is that they wanted to talk about hip hop and nothing else. And those who are calling themselves music journalists and critics (and there are a lot who pass through my classes or my office) are committed to writing about hip hop and popular music, but not much more. Our collective musical literacy is quite low.

Let me propose one other explanation, and this moves us into the next question. For about three years, thanks to John Rockwell, then editor of the New York Times Arts and Leisure section, I contributed several pieces to the Times. He generously invited me to write because I was pushing for more diverse voices on that page. I never felt censored or pressured to do anything, and I always worked closely with an African American editor on the paper named Fletcher Roberts. I understood how privileged I was, especially given how few of us were writing for the Times. But then I proposed writing a piece about the history of jazz in Brooklyn and its renaissance in the community throgh various clubs, churches, and the Central Brooklyn Jazz Consortium, among other things.

I had a ball with the piece and the main argument or discovery was that black folks in Brooklyn were taking jazz back through cultural institutions that are not necessarily on the downtown radar [editor’s note: again, see Ron Washington’s piece in The Independent Ear]. The piece was written and ready to go, but then John Rockwell was replaced by then 28-year old Jodi Cantor and she nixed it, said something like "who is going to believe black people are so into jazz" or it could have been "who cares?" I don’t remember; all I know is that my writing for the Times ended then and there.

Do you think that disparity or dearth of African American writers contributes to how the music is covered?

The last part of the [Brooklyn jazz/NYT] story party answers this question: to put it more directly, in some cases, black writers want to look at questions of race, politics, power (not always!), and place this music within its broader context [editor’s note: Precisely the reason for The Independent Ear!]. I’ve found some resistance to this, mainly from those who think music is pure and that any discussion of politics, race, and power is an imposition. What I do find interesting is how eager many musicians are to discuss these issues.

Since you’ve been writing about serious music, have you ever found yourself questioning why some musicians may be elevated over others and is it your sense that has anything to do with the lack of cultural diversity among the writers covering this music?

I’m not sure I can answer this question with much authority. While I do write about serious music, I do so as an historian rather than a critic. I don’t write reviews of shows or recordings, and the few times I have written on contemporary developments in the music (like my piece on DJs and jazz for the New York Times nearly 10 years ago!), I hardly pay attention to what critics are saying about the contemporary scene. In other words, I don’t know who is being elevated over whom at the moment, except when I listen to the jazz station in Los Angeles (KJAZ) and I have to endure endless recordings by Jack Sheldon but virtually nothing by Thelonious Monk, let alone Cecil Taylor.

I know in principle that lack of cultural diversity has a negative impact on any kind of writing or critical engagement. The lack of intellectual diversity does, too. What I mean is that not all writers are critics, and some times the issues are not about who is better than whom, but what is a particular artist trying to do and what does it teach us about the music and the world we inhabit. This is exactly why I appreciate the work of Stanley Crouch and Baraka, not to mention Robert O’Meally, Farah Jasmine Griffin, John Szwed, Guthrie Ramsey, Krin Gabbard, George Lipsitz, George Lewis, Eddie Meadows, Kyra Gaunt, Tammy Kernodle, Salim Washington, Dwight Andrews, Eugene Holley, you, and many, many others who are trying to say something other than this is a great record, this is not.

What’s your sense of the indifference of so many African American-oriented publications towards serious music, despite the fact that so many African American artists continue to create serious music?

It is unfortunate, but has been going on for some time I think. Having just finished Monk’s biography, I have scoured the black press for material — again, almost always ignored by other writers, scholars, biographers, etc. — and found what I think of as a forgotten legacy of black jazz writers. We need to deal with Rhythm magazine, a black-owned but short-lived publication that my man Eugene Holley hipped me to. Herbie Nichols wrote for them (and he wrote a regular column for the New York Age), as did John R. Gibson, among others.

Few know about Nard Griffin’s little book To Be or Not to Bop? published in 1948 (Dizzy stole the title for his memoir from Griffin). We haven’t paid attention to the brilliant critical writing of Frank London Brown, better known to us as a novelist but he was also a fine jazz writer and excellent singer himself. I could go on. There were also many black women writing about this music in the black press. Most people never heard of Eunice Pye of the L.A. Sentinel, or Joy Tunstall of the Pittsburgh Courier, or Phyl Garland of Ebony. But over time black publications withdrew from writing about this music and instead fell for the celebrity trap. I think they thought they were losing their readership and, truth be told, they were competing with mainstream magazines and newspapers that had their own critics.

I give it to Joanne Cheatham, who [is trying] to get something out there with her publication *Pure Jazz [editor’s note: the Summer ’09 issue of the Brooklyn-based Pure Jazz is currently available; purejazzmagazine@aol.com]. But I don’t know how well she [is] supported. I wrote a couple of pieces for it, but if we don’t support our publications and demand that others pay attention to this music, it just ain’t gonna happen. I won’t go on, but I will say it is disgraceful how someone like Oprah just has no interest in serious music, to name one example.

How do you react to the contention that the way and tone of how serious music is covered has something to do with who is writing about it?

I began to answer that question [earlier]. I will say that I think it makes a difference, but I will not say that race is always determining. Political worldview, experience, knowledge, cultural perspective — all these things matter.

In your experience writing about serious music what have been some of your most rewarding encounters?

Always meeting and getting to know musicians. Through interviews and inquiries, I’ve made many friends with some amazing artists, and nearly everyone demonstrates a level of generosity and intelligence that hardly comes across in the mainstream reviews. I can name many, but the relationship that has been most transformative for me has been getting to know Randy Weston. I’ve always loved his music since I was a teenager but meeting the man, benefiting from his insights, his deep commitment and love for all people, especially Africa and its immense history, his politics and deep knowledge — he’s like the father I wish I had. He is a model musician and composer and a model human being who always has kind and thoughtful things to say. And he’s down with the people!

What obstacles have you run up against — besides difficule editors and indifferent publications — in your efforts at covering serious music?

You named the biggest obstacles! For me things are slightly different since I’m not really a critic and more of an historian. I focus on rethinking and revising the history of serious music, thus sources continue to be a problem. We need more archives and oral histories (and good work is being done now, by the way). It is incredibly hard to write this history, especially those artists who have remained under the commercial radar. I think about George Lewis’s magnificent book on the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) and what a tremendous contribution he made. Just look at the footnotes and you’ll see why it took so long and just how hard he had to work to reconstruct that story. Brilliant book. My book on Monk tries to do the same, especially when I try to give little capsule biographies of the folk who rarely make the history books — like Little Benny Harris and Denzil Best and Danny Quebec West and Vic Coulsen, or even the better known figures like Herbie Nichols. I fought hard to tell their stories, and the reviewers will complain about the dizzying detail in my book. But these stories have to be told, and reviewers, editors and readers don’t have the patience to engage the bigger, more truthful picture. It’s easier to play into the cult of individual and write about what’s genius and jacked up about an artist, not the community that made the artist who she/he is.

*The editor has an interview with the brilliant South African vocalist Sibongile Khumalo in the Summer 2009 issue of Pure Jazz magazine.