Do Jazz Artists enjoy longer artistic lives?

AHMAD JAMAL

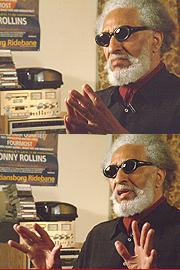

SONNY ROLLINS

Years ago when Suzan Jenkins was the exectutive director of the Rhythm & Blues Foundation, which at the time was based in DC, their major annual event was the Pioneer Awards. This was the annual occasion on which the giants of R&B were given well-deserved recognition in the form of Pioneer Awards, accompanied by a check, which was more times than not much-needed. In the beginning the RBF limited its Pioneer Awards consideration to those R&B artists who had an impact (i.e. hits) in the 40s, 50s, and 60s. More recently the RBF has expanded that stipulation to award artists of the 70s as well.

Several things were always quite striking about those awards. Looking around the room and surveying the stage when the various awards recipients and awards presenters as well would happily bound up on stage to receive their awards and perform their signature songs to the strains of a great house band (often led by Maceo Parker and including such masters of the form as Steve Cropper on guitar, himself a Pioneer Award winner the year Booker T & The MGs copped, and the funky drummer James Gadsen; the band also included "ringers" like Hamiet Bluiett on bari sax), I always had to chuckle to myself a bit at the vanity factor; despite the fact that we were exclusively talking about artists who by then were card carrying senior citizens, there wasn’t a gray head in the house! But these were the artists who gave wing to so many of our teenaged years that we forgave them that vanity. I remember one singing group member actually had on such a bad hairpiece that its shape comically resembled a Kangol cap! The women came decked out as if they were about to put on a Vegas show and it often resembled a wig convention on the female side.

This constant quest for the youthful appearance of yesteryear underscored one sad but salient fact: these were artists whose flames were extinguished in their relative youth, long before their artistry had an opportunity to ripen. These were artists whose work had once almost exclusively served a youth audience, who once they either surpassed the youth of their audience or the hit factory dried up were simply cast aside for the next flavor of the moment. And as I listened to the various heartbreaking trials & tribulations of so many of these artists whose rocket ascent to the "top" was just as suddenly accompanied by an even swifter descent to the bottom, I saw how fleeting fame can be in our throwaway society. The truly heartbreaking pathos would come when I’d hear about some supposed giant or other who I had assumed must have lived the figurative life of Riley in a rarefied air most of us can only dream of on the wings of those million sellers, gold and platinum records alike, needing to have their funeral and burial costs paid by the RBF because they wound up broke and relatively destitute. I can also remember how we’d awaken the next morning to persistent telephone calls from Pioneer Awards recipients looking to hungrily cash those awards checks.

Artists whose major hits might take two hands to count needed bailing out when the Grim Reaper called! I’ll never forget the melancholy story of a fallen diva from my dance party youth whose family insisted that the RBF not only fund her services and burial, but that she must have several changes of clothes for her funeral home viewing services! We’re talking about someone who has passed, not some poor soul needing a new suit to make a job interview! These elements just brought to mind the fleeting aspects of what we think of as fame; the fact that such artists’ fortunes are tied to a youth culture and a youthful existence (and appearance) that cannot and does not last; artists who are just as quickly kicked to the figurative curb as their sudden rocket to fame. This is the pop life I’m afraid; here today, gone tomorrow.

I’ve often thought of that as my work with the NEA Jazz Masters program proceeds and as I communicate with so many senior jazz artists. In jazz we are perpetually wailing about our relative lack of recognition, the constant struggles of artists making this music, and about the second class citizenship of the beloved art form in the larger scheme of the music industry. However the fact does remain that for those who are blessed with perseverance and longevity, the rewards of jazz mastery can sustain. Fortunately we in the jazz community are not about casting aside our legends once they’ve gone gray and are no longer producing "hits." We tend to honor longevity, youth has to prove itself over time in this music; the attrition rate may be significant, but elderhood does have an honored place in jazz, so unlike the pop forms.

I thought about that on two life-affirming recent occasions when being in the company of a couple of jazz masters was truly uplifting. The week prior to Thanksgiving the occasion was a site visit for the NEA Jazz Masters Live program component. The site was Baton Rouge, LA for the Arts Council of Greater Baton Rouge’s engagement of Ahmad Jamal, 79. Its been a real pleasure and a privilege visiting some of the sites of NEA Jazz Masters Live-supported programming, but the first evening of Jamal’s two days in Baton Rouge was rather unique. The CEO of the Arts Council of Greater Baton Rouge is Derek Gordon, formerly of the Kennedy Center and Jazz at Lincoln Center. As a prelude to Ahmad’s arrival Gordon presented a program consisting of student ensembles from Southern University, Louisiana State University, and the famed New Orleans Center for Creative Arts (NOCCA) playing some of Jamal’s compositions and music associated with the pianist in their own arrangements.

On the Wednesday evening of Ahmad Jamal’s visit Gordon arranged for those student ensembles to reprise their performance of his music for Jamal himself. I watched intently as Jamal quietly studied their performances, taking notes and observing patiently. At the end of each piece he gave his cordial approval in a fairly non-commital way. If you know Ahmad Jamal you know he’s a man of great conviction and strong opinion. So I kept waiting for some broader response. Instead Jamal surprised us all at the end by generously requesting that each band director provide him with the email address of each student musician so he could send them a personal email with his response to their playing!

The next night Jamal played two shows before full houses at the intimate and shiny Manship Theatre. Being in Louisiana gave Jamal a chance to further reflect on how important New Orleans drumming has been to his music, considering that New Orleanians Vernel Fournier, Idris Muhammad, and Herlin Riley were his longest-tenured trapsmen. Don’t forget, what truly made "Poinciana" the monumental hit it was for Jamal was Fournier’s distinctive New Orleans drumming. On this evening Jamal renewed that Crescent City connection by employing another New Orleans-bred slickster, the ever-youthful vet Troy Davis, on the tubs. This was the first time Davis, currently living and teaching in Baton Rouge, had locked up with Jamal but one would hardly have known it given the loose-limbed lockstep he fell into with Ahmad’s characteristic use of open space, keen sense of rhythm and pacing, and distinctive brand of bandleadership. That evening’s obligatory performance of "Poinciana" felt as fresh as it must have when Jamal first hit it at the old Pershing Lounge.

Afterwards I asked Davis, who was visibly uplifted by the connection (and Jamal plans on engaging Davis again) how he was so quickly in synch with Jamal. Troy Davis: "I’ve been playing drums for 40 years, even though I’m still young (laughs), but that doesn’t mean anything when you’re playing with Ahmad. You just have to watch him, it’s as simple as that, you just have to watch him and pray… anticipate and pray… You know what makes it easy? He gives you cues, he’ll tell you when to start and when to stop, but then you have to fill in everything else in the middle. But his time is impeccable…"

The week after Thanksgiving came another senior sighting when the Saxophone Colossus Sonny Rollins, also 79, touched down at the Kennedy Center Concert Hall through the auspices of the Washington Performing Arts Society (WPAS). No longer the road warrior he once was, Sonny picks & chooses his dates and frankly commands a fee (God bless him!) that is beyond the reach of many jazz presenters. So when Rollins comes around it is event programming, and this evening was no exception. The huge KC Concert Hall was jam packed with anticipation and one sensed that the audience was there in appreciation of royalty; a fact substantiated by the standing ovation when Sonny ambled onstage, before he’d even played a note. And his 90-minute+ performance did not disappoint. Years ago critic Ira Gitler famously characterized John Coltrane’s tenor improvisations as "sheets of sound". In Rollins’ case that would be torrents of sound, a different approach to tenor mastery than his old friend Trane, but no less potent. The closing de riguer "Don’t Stop The Carnival" (one of only two calypsos on this evening, for those who keep score and look askance when in their estimation Sonny dips in the calypsonian well once too often), was truly ecstatic, with many in the audience dancing at their seats. Sonny was perhaps more gregarious and expansive with his audience, eliciting shouts of recognition when he reminisced about his boyhood times in nearby Annapolis, MD and his unrequited 12-year old crush on a 19-year old. One piece I’d not heard previously was an original he wrote in tribute to J.J. Johnson, at the end of which he raised his arms and sang a vocal coda!

These two rich experiences simply served to bolster the sense that in the right hands, and given the right life circumstances, the jazz crusade is a lifetime quest for the persevering practitioner — and thank goodness the jazz audience is not about throwing away the flavors of yesteryear! So to all of you young musicians struggling with your music, and struggling even harder to attain jobs and a healthy audience, remember… perseverance can pay off in jazz music, and indeed have its rewards.