I referred to you as an artist manager, you prefer Artist Development Mentor and Rights Activist. Please detail your work in that regard.

I officially became an artist manager in 2003, when I was working as a festival programmer in Detroit for Movement (Detroit’s Electronic Music Festival). I met a number of incredible artists who needed help getting their music out there to international markets, and as I worked internationally most of the time, I could provide a good route to markets outside the US for a number of artists. When I came back to the UK, I brought the artists’ demos and albums, then eventually got them out there. Amp Fiddler was my first bonafide management client, who I was with for 12 years, and over the years I worked with a number of artists across soul, hip hop and jazz, including Amp, Incognito, Tortured Soul, Stephanie Mckay, John Arnold, Ayro, Sixto Rodriguez, Shuggie Otis, Marc Cary, and KING, to name a few. Prior to that, my background had been in live event production and booking, and cataloguing reissue labels intent on documenting the black roots of modern dance music and marketing it to a dance generation. I worked on notable reissues for Strut records as well as working on curated presentations and tours with artists as wide ranging as Marlena Shaw, Martha Reeves, Hypnotic Brass Ensemble, The Detroit Experiment, Rakim, Big Daddy Kane, Sly and Robbie, Grandmaster Flash, Leon Ware and more. I got into all of this when I was finishing up my PhD in the mid 1990s, and supplemented my research by DJing and running clubs in Scotland centered around jazz (where we would bring artists like Weldon Irvine, Charles Earland, Wilton Felder, Reuben Wilson, Gil Scott Heron, Jalal The Poet,and more). I also worked extensively for the Scottish Jazz promoter Assembly Direct managing their festivals and regional tours, as well as working in the booking and marketing departments of London’s infamous Jazz Cafe.

In all manifestations of my career, I came across rights issues for the artists. Whether it was unpaid royalties, copyright infringements or basic bad deals.

There’s been a trend over the past few years for the manager to effectively be the dumping ground for all roles that don’t fit into a traditional industry bracket, and as an independent manager, I realized I could only ever really effectively help one or two artists at a time. But because I have spent a lot of time over the years helping a number of artists sort out royalty and copyright issues, and I also work with more and more entirely independent artists, I see a bigger problem at play. When an artist brings a piece of music to the world, many different copyright revenue streams are created, but our industry is still woefully backward in recognizing what this means to the artists. When I can talk to an 18 year old artist and they have nearly identical issues as an 80 year old artist, there’s still a few issues we need to address as an industry. So I felt I needed to make a very deliberate shift away from the traditional idea of a manager and move to a more service based artist development model, while advocating for clear and transparent rights management in our industry.

Right now, I have more than 25 consultancies in place, some pro bono, some paid, but already in 12 months, I have managed to reunite, maintain or register 20 plus artists and counting effectively where they need to be, as well as get rights and equity back for some more seasoned artists with multiple releases.

You’ve apparently identified rampant disparities in rights issues where jazz artists are concerned. What disparities have you determined to remedy?

I could literally write a thesis on this, but I will try here to give you the broad strokes. There is still an inherent lack of understanding with a lot of artists who record their own works, how they actually access their mechanical income. Every day, I can talk to a US Jazz or hip hop artist who will tell me “BMI collects my mechanical income, I am a publisher there” – this is not what BMI, ASCAP or any other performing rights society does. This is the most fundamental building block of a musician/composer accessing their income. Next you have the age old problem of neighboring rights. This issue for 50 plus years has hit US artists and in particular US Jazz artists the most. The lack of America being part of the Rome Convention, and it taking the US over 100 years to join the Berne Convention that gave international performers moral rights in other countries have hit the musicians here hard. A lot of the practices that are common in the US music industry are prohibited by European Copyright law, and across the industry here (but I find it rife in Black American music). It is frequently exploited by independent and major labels who negotiate these rights away from the performer. In the rest of the world, these rights are unalienable, and can only be transferred away in death and bankruptcy. I’ve been living in New York six years now, and I find that a lot of my colleagues in Jazz either don’t understand this stuff, or think it doesn’t affect them. But given the historical predominance of physical product and European sales in Jazz, it affects our beloved US jazz musicians even more! This will be more and more problematic as the new laws come in in 2020. There will be more than 6 PROS, numerous mechanical intermediaries, and more and more digital steaming platforms offering direct access and generating new rights for the artists. We need to address this now. It’s not streaming that has ” killed” the jazz markets, it is all of the above.

With the US having a very different Rights system, unless you know how to navigate clearly around registering your data, or what societies to join and which mandates for which markets you should sign, it’s easy to leave money sitting on the table. In addition, many of our jazz artists young and old have money sitting in industry black boxes, generated from performances and other digital rights. For instance, AFM, SAG, AFTRA frequently have money that the artists are owed for performances. This fund deals with royalties generated by non-featured artists which are paid through to them via Sound Exchange. Problem is, they don’t have an efficient mechanism for connecting the non-featured artist to the performance. A lot of artists leave it sitting there because they either don’t know about it, or they are not given the correct information when they get to the union to pickup an unclaimed check.

The more controversial aspect is the type of deals that artists are still frequently seeing in jazz from “reputable” independent labels, that are more akin to the deals which were getting done between the 1950s and 1990s – many artists old and new are still suffering because of exploitative deals from labels who either simply don’t know or don’t want to know better, or ones who simply don’t care. As we have an aging group of professionals as well as artists in jazz, a lot of the same people who were making bad deals in the 1990s are still making bad deals today. There’s been a big outcry this week about Tommy Boy Records hitting De La Soul with a 90/10 deal, and an entire industry has stood up in De La Soul’s defense, including major streaming platforms such as Tidal. In Jazz, we frequently see 80/20 even 90/10 deals for perpetuity, and worse, like labels insisting upon taking an artists publishing or performance generated income on top. These are barbaric deals and a huge part of the reason artists are starting to abandon traditional labels and platforms to do it themselves. As an industry, we need to talk about this.

What is your sense of artist’s need to record their work and what is necessary to maximize the potential benefits of recording their work?

I think it is so important for artists to document their work by recording, both in the studio and the live arena. The liner notes, the credits… This stuff is so important.

Also stuff like where you record. Like every US artist would instantly make more performance income if they didn’t record in the US, but recorded in a territory governed by the Convention of Rome.

We have more and more technology at our disposal to manage recordings and meta data efficiently.. I also don’t think this necessarily means having to move away from th expertise of producers and high quality studios and such, but we do also live in a time now, where you can literally record an album at your kitchen table, and be nominated against Beyonce for a Grammy!

The key to maximizing and generating revenue from these endeavors is meta data and knowing where income is generated and how you collect it. There are both traditional and new ways to do this but it has never been easier to input metadata correctly and get it where it needs to be, and get transparent reporting as it is all binary driven electronic information.

DIY platforms these days have tech that far out strips anything a label can do for an artist directly. One of the biggest problems for signed artists is that often the responsibility for registering metadata is with the label, and as most labels are entirely self-serving, they are not going to care as much as the artist about the other revenue streams they cannot collect. The more unscrupulous will also take advantage of this. I am currently battling one label right now. We discovered that label had registered one clients’ copyrights with the US copyright office with themselves as the exclusive copyright claimant, despite the fact it was a license deal and not a buyout. This is hugely problematic, even if it initially stemmed from a place of ignorance rather than exploitation by the label. The hardest thing in a copyright claim is to prove someone doesn’t own something, rather than proving that you do.

We have many established artists who struggle with all of this, and we have a growing number of new artists, some even coming out of music school who struggle too. Something is wrong with this picture.

The other key factor is acknowledging that release cycles are no longer a 3-month game based around coordinated release of product and formats. Modern day release cycles are long-lead with sales and promotion a continuous flow, not the purchase driven model that we have become accustomed to.

With or without the labels, the artists can now drive plays from virtually every fan interaction. Record labels need to be working hand in hand with their artists to understand this data and grow from it. If we invest in this as a community, we foster creativity and gain traction from the intel we amass.

Labels need to stop thinking like companies selling music and start thinking about their agency in nurturing an artist’s creativity and help them streamline their meta data so they can gain every revenue stream available to them.

Music discovery and consumption have never been more immediate or closer to each other. In the US Jazz industry, there is still a tendency to work to an 8-12 week release cycle (which is partly why more and more artists move away from this practice.) When you work this way, you fail to benefit from the fact that you can now monetize engagement as much as the consumption of music.

Is it your sense that artists benefit more readily from recording their own product, or would a more equitable relationship with a recording company be more in their favor?

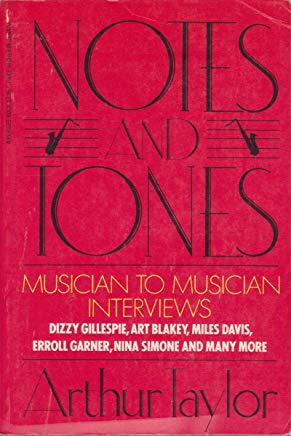

I love that you asked this question. Yes yes and yes. This is the very same question Arthur Taylor posed to many of his peers in Notes and Tones – artists we all love, like Ron Carter, Randy Weston, Charles Tolliver, Hazel Scott, Betty Carter and more were discussing exactly this at that time around 1969-1971 because of the disparity between fair record deals and getting their music out there.

What a lot of people may not realize these days is a lot of artists even signed to labels are not just having to walk in with a demo to get a deal – they are already a lot of the time front-ending the recording costs and taking finished masters to labels in a hope the label will take it. But yet they still often get faced by these outdated and unfair deals. They get told “now you have to pay for radio and PR” and then after all that, if it doesn’t work, the artist becomes the perfect scapegoat for why it didn’t work. We get told such things as “no one buys jazz anymore” Which is completely untrue, but we have to trust people who think this way to sell the music. We also get told “radio needs CDs” or “send 500 cds to press”, but the sales cycle has changed, digital nearly always comes first these days, and the opportunities in the US for coverage in jazz media and radio are diminishing every day. But we have other areas of growth, and we have artists’ apps which now help us monitor just what our labels are doing, so there is definitely a movement to going where the love is.

I know some people will think that my views are anti industry but I strongly believe in all the good that has come from traditional areas like A&R, production, label and publishing culture, and I hope the independent sector doesn’t get too detached from being able to access these areas of expertise. But you’d be hard pushed to find a jazz label in the Mecca of New York, which still upholds these values themselves, or are even capable of bringing them to an artist.

The model has to shift to a license-driven cooperative model of artist development, where artists retain their rights, in order for labels to remain viable, otherwise we just perpetuate a highly flawed system which no one is taking responsibility for.

Talk about some examples of artists who have taken necessary steps to remedy this recording connundrum.

My company, Intrinsic Artists, set up a project called We Roar, which is currently Fiscally Sponsored by Fractured Atlas. We have been offering pro-bono services to some of our most beloved jazz artists to help them rectify collection issues, particularly on neighboring rights. In partnership with a company in the UK called Traxploitation, we have commenced working with notable names such as Gary Bartz, Reggie Workman, Roy Ayers, Tarus Mateen, Marc Cary, Cheick Tidiane Seck, Marlena Shaw and Jimmy Cobb to reconnect them with missing income. Thus far between Gary Bartz and Reggie Workman alone, we have registered in excess of 1000 featured, sideman and sampled performances in the international markets, as well as assisting them reclaim missing payments sitting at the various US unions. With Roy, there are over 1500 titles we are in the process of registering and the list keeps getting longer of artists who need this type of help. The work we have done to date gets them into the distribution cycle for June internationally, so a lot of them will see royalties going back 6 years for music they have never seen income on. We are working to have even more fully registered for the winter distributions. Each year that gets missed, the artists lose a year of money. For someone 6 decades deep in the industry, that’s a lot of money!

We are also working closely with many established and up and coming artists such as Canadian Harlem-based drummer Curtis Nowosad, vocalists Emily Braden and Jackie Gage and our collaborative recordings borne from The Harlem Sessions. Truth be told, none of these artists are cutting corners- they are renting recording studios, paying their musicians, and trying to raise funds constantly to pay for Pr and marketing. Some who are more adept to other digital techniques use them in the home studio. Some sample their live recordings. The possibilities are endless, but the investment is huge, which is why the issues and obstacles truly need to be addressed.

Finally, we are in the process of helping certain artists get their masters back from deals which have either expired, or where the labels have stopped accounting to the artists (which should never happen). We recently got Marc Cary’s first album back, which we are slating for a remastered issue in 2020, and we are working on many many more. There’s nothing worse than hearing multiple jazz artists every day who you love from every decade tell you a tale of a label who stopped accounting to them, or someone who got in the way of them getting their money or did a bad deal which they couldn’t afford a lawyer to look at. A lot of the same labels still exist today and they are still doing the same thing. A lot of them are indies. Difference is now, we have technology and user-generated forums which help the artists measure the extent of the problem better, before wading in with lawyers and auditors. I have to stress, I speak from very specific artist experiences, rather than approximately an average idea that every label operates this way. But many do, and that’s another piece of the puzzle we are trying to help resolve so our artists don’t suffer so needlessly in later life.

2 Responses to Standing up for artists beyond the bandstand