Our correspondent for this edition of the series Ain’t But a Few of Us: Black jazz writers tell their story is Bridget Arnwine. I first encountered Bridget in 2005 when the Jazz Journalists Association sponsored a one-time fellowship award in the name of the late African American jazz writer Clarence Atkins. The fellowships were awarded to a small group of deserving, aspiring African American jazz writers enabling them to attend the National Critics Conference in May ’05.

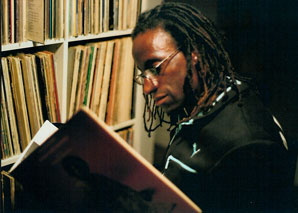

BRIDGET ARNWINE

The young writers who participated in that fellowship opportunity were Bridget Arnwine, Laylah Amatullah Barrayn, Michele Drayton, Robin James, and Rahsaan Clark Morris (whose contribution to this series will be posted soon). Since then Bridget has continued to develop her writing craft; she spent a few years working in the Cleveland area, where among other things she wrote the program book copy for the annual Tri-C JazzFest. Recently Bridget relocated to the Washington, DC area where she continues to write and work her new 9-5.

Per usual, our conversation began with an inquiry on what originally motivated Bridget to write about jazz in the first place.

I’d met Wynton Marsalis in August of 1995. Up to that point all I knew about jazz was Kenny G. I was more intrigued by hip hop, r&b, and rock music than anything else; in my mind jazz was something for other people to enjoy.

Over the next few years, my friendship with Wynton blossomed and as a result I began to seek out the music. I could always call Wynton up and ask him questions and even though I wasn’t a musician I found that to be an invaluable experience. Then I got to see him perform with guys like Eric Reed, Victor Goines, Herlin Riley, Wycliffe Gordon, and Wess Anderson. They played like they really, really enjoyed the music. I’d never experienced anything like that… Ever. None of those guys would be able to pick me out of a lineup if I were standing in front of them today, but I’ll never forget them because meeting them changed my life.

It was a long time coming, but when I finally did fall for jazz I fell for it pretty hard. I don’t sing. I don’t play an instrument, and my dancing is wild and unstructured at best. About 7 years ago I began to feel an urgent need to express my love for this music. I came up with the "brilliant" idea to write a book comprised of interviews with jazz musicians. I began to contact musicians and publicists requesting interviews. The only person to say yes was Wynton, but I didn’t have a book if my book of interviews consisted of interviews with one person! As a last resort I contacted Wynton’s personal assistant and asked for guidance and she gave it to me! She suggested that I take time to first build my writing resume, so I joined the Jazz Journalists Association and I started writing reviews. I’m a bit shy and over-analytical, so in actuality the review/bio writing route was a better fit for my personality.

When you started on this writing quest were you aware of the dearth of African Americans writing about jazz?

No. When I first started writing my motives were purely selfish, so I had no idea. I figured it out pretty quickly though.

Why do you suppose that’s still such a glaring disparity — where you have a significant number of black musicians making serious music, but so few black media commentators on the music?

In my opinion, black writers are going where the money is and that certainly is not in jazz’s direction. I write about jazz because I’ve come to love it, but it’s hard. A lot of the work that I’ve had to do in my 6 years as a writer has been for free. Who can afford to do that? I don’t want to work a 9-5, but I have to in order to sustain myself. That’s not to say that every black writer covering this music has the same experience, but starting out can be tough. Couple that with the fact that black audiences for jazz are typically small. When you look at it that way, then the small number of black writers makes sense.

Do you think that disparity or dearth of African American jazz writers contributes to how the music is covered?

Definitely. I write with a bit of emotion, because I have to rely more on describing how the music makes me feel than does a writer with a musical background. Some of the people who have worked as editors for me usually don’t get the gist of my work, so I’m always struggling to preserve the uniqueness of my voice so that my writing doesn’t sound like everyone else’s. It’s a challenge, particularly when you have to adhere to someone else’s writing guidelines. A funny example of that for me involves my time writing for a heavy metal webzine. I always discussed the music and my thoughts on the band and I always threw in a few funny little extras, but my reviews were heavily edited because to them my writing was "too professional" sounding. I’ve yet to have a jazz editor tell me that about my writing!

Since you’ve been writing about serious music, have you ever found yourself questioning why some musicians may be elevated over others and is it your sense that has anything to do with the lack of cultural diversity among writers covering the music?

I do sometimes wonder about that… I was thinking recently aboput the negative press that some of our African American jazz icons received during their lifetimes. Before I really got into the music I had heard that Miles Davis was a jerk and that Charlie Parker was an addict. I’d not heard a lick of music from either of them, but those statements were discussed around me more than their music and that’s unfortunate. On the other hand, about a year ago I read something about Stan Getz and there was mention of his drug abuse and the extent of his physically abusive behavior toward his second wife. I remember being shocked, because I’d never heard anyone mention that when talking about Mr. Getz. Clearly someone covered it, because I did read it, but I wondered why that aspect of his personality wasn’t discussed on the same level that Miles and Bird’s issues were. Was it because of the lack of diversity among the writers covering this music and its artists? At the time I couldn’t help but think so. To that end, however, I do thnk Miles and Bird were celebrated for their musical achievements more than I think Getz was, so I don’t know how to process that.

What’s your sense of the indifference of so many African American-oriented publications towards serious music, despite the fact that so many African American artists continue to create serious music?

It goes back to my thoughts about money. Jazz music — and serious music of all genres — is largely not popular. Popular music is what sells, so that’s what you find discussed in those pages. I would think that the African American oriented publications would be a place where jazz musicians and less popular but equally talented musicians from other genres would have a home, but I guess money is money.

How would you react to the contention that the way and tone of how serious music is covered has something to do with who is writing about it?

I’d say that I think that is right on the money. When more writers of color start covering jazz, then I think things will change.

In your experience writing about serious music, what have been some of your most rewarding encounters?

Some of my most rewarding encounters involve just seeing people’s faces when I’m introduced as a jazz writer. I’m a very brown woman, but I’m 100% certain that I turn red when that happens! It’s an awesome feeling! I also love it when I find my work on an artist’s webpage or in a press kit. That’s pretty cool too. I’d love it if I were called soon to cover a festival! Oh what a happy day that would be! I’m claiming South Africa, Monterey, and Umbria…

What obstacles have you run up against — besides difficult editors and indifferent publications — in your efforts at covering serious music?

One obstacle that I’ve faced is being unknown AND being a woman of color. There was a time recently where I’d written a book review that wasn’t received very well. I liked the idea of the book, but I thought it was poorly written and poorly edited. I struggled with this, because the author of the book was a woman and she has been around for a long time. I contacted the [publication] editor about how torn I felt over wanting to write an honest review without being offensive and he advised me to just be honest. I had the misfortune of making a mistake in my review (I incorrectly noted the wrong college when referencing the author’s alma mater) and I really, really beat myself up over that mistake. Here I was critiquing someone else’s book (a book that people would have to purchase to see the errors I’d pointed out) and i made my mistake in a free publication!

When my review was published the editor I worked with was bombarded with emails from the author and he happened to share some of those emails with me. He wanted me to be prepared in case the author decided to reach out to me personally. The emails turned into an official Letter to the Editor! I was advised not to respond and, even though I really wanted to, I followed the advice and did not respond. Surprisingly, the author only mentioned my mistake once and it was in passing. What really seemed to set her off was the fact that I didn’t like the book. What stung most about those emails and that letter was that she said (when referring to me) "at least she’s not one of us." Just like there aren’t many writers of color covering jazz, there are probably just a few women. I’d never met this woman, so I don’t know that she surmised that I was black, but I was left with a bad taste in my mouth over that "not one of us" comment. To read those comments coming from a woman really hurt, particularly when I’d gone out of my way to not be negative in my review of her work. I’d never felt like more of an outsider than I did after I read her words. I ended up taking another hiatus from writing and I’m just now starting to feel like I want to write again.

If you were pressed to list several younger musicians who’ve impressed you who might they be and why?

I really like Esperanza Spaulding, Sean Jones, and Jason Moran. While I think Jason Moran is fairly accomplished, I’m including him in my list beause I think he’s on the verge of being included in the long list of greats on his instrument. He’s really interesting and I like his music. Esperanza Spaulding is also really interesting, because she sings and plays bass. I’ve met a few female bass players, but I haven’t met any who sing. I’m exicted to see her career unfold.

Sean Jones is just talented. It would seem that he’d have a harder path than the others, because he’s a Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra trumpeter and he works closely with Wynton Marsalis, arguably one of the most famous jazz musicians the world has ever seen. Sean has recorded a lot of music and accomplished a lot at a young age, so I don’t think he’s paying attention to any real or perceived obstacles. His talent is undeniable and I say get out of his way. I received an email request to review a CD for Orbert Davis and the Chicago Jazz Philharmonic. I listened to their music online first and was blown away by what I heard. I suspect that they will definitely get lots of acclaim in the future.

I also interact with a lot of musicians online. I’ve encountered some really talented folks like a sax player out of Chicago named Chris Greene. He plays with an infectious enthusiasm that I think is great. He’s so hungry and I love hearing that. Hearing him reminds me why I love music! Doug Wamble is another guy that I’ve interacted with online that I think has tremendous talent. He’s signed to Branford Marsalis’ Marsalis Music label and I think he’s on the verge of something great. Then there’s a singer named Teressa Vinson who actually holds a PhD and teaches Psychology! She has a soft and pleasant voice. If she were able to dedicate more time to music and get with a great producer, I think she’d be a force to be reckoned with. There’s another guy named Leigh Barker who’s a bassist out of Australia. He also has a pretty cool sound. I know I’m missing some musicians, but it’s exciting to know that there’s so much good music out there.

What have been some of the most intriguing new records you’ve heard this year?

I’m just coming out of my hiatus, so I haven’t had an opportunity to listen to much this year. I will say that I really loved "He and She" by Wynton Marsalis, "Collective Creativity" by the Chicago Jazz Philharmonic, "Metamorphosen" by Branford Marsalis, and "Bossa Nova Stories" by Eliane Elias.