Reflections on the Left Bank Jazz Society

By Willard Jenkins

The history of jazz societies in the U.S. dates back to the mid-20th century. These have generally been organized clubs or gatherings of jazz enthusiasts for the purpose of discussing and enjoying jazz together, whether that be attending live performances or discussing jazz recordings in some organized – often scholarly – fashion. Jazz is a communal music in many ways. It’s a music, which at foundation is characterized by the band or ensemble of varying sizes, with musicians interacting and improvising together through a pre-arranged blueprint or arrangement, or perhaps in expressions free of pre-ordained structure, but interacting cooperatively nonetheless.

Likewise jazz enthusiasts, in part due to the somewhat exclusive nature of the audience for jazz and the fact that jazz has not since the 1940s been a mass consumption music, have often felt compelled to gather with like-minded folks for the enjoyment and promulgation of the music. The best, most successful jazz performances are characterized by that successful interaction between a band or ensemble of musicians – often a sort of rhythmic gravity referred to as “swing” – performing before a spirited audience that expresses their delight in applause, vocal encouragement of the soloists and the band, and that good feeling generated among an audience when the sense of group enjoyment is palpable in spirit. It is this sense of communal spirit, coupled with the fact that jazz music enjoys smaller, often more dedicated audiences than mass consumption music, that has compelled jazz enthusiasts to develop some form of organizational vehicle to further express their deep appreciation for jazz music and the musicians who play the music.

I’m happy to say I had my own jazz society experience. Living in Cleveland, OH where I grew up, a few years after my undergrad days when I was working full-time and on the side developing myself as a jazz writer and broadcaster, we had a great jazz club called the Smiling Dog Saloon. That particular club, which began presenting live jazz in 1971, featured many of the touring greats of jazz; for me it was the first place I experienced Miles Davis, Sun Ra, the Thad Jones-Mel Lewis Orchestra, McCoy Tyner, Cannonball Adderley, the Gil Evans Orchestra, the original Weather Report and Return to Forever bands and many others. Due to a variety of circumstances the Smiling Dog closed its doors in 1975. Believe me, this left a real void in terms of touring jazz greats playing Cleveland.

Joe Mosbrook has written a definitive history of jazz in Cleveland, including the Northeast Ohio Jazz Society’s development

Joe Mosbrook has written a definitive history of jazz in Cleveland, including the Northeast Ohio Jazz Society’s development

In 1977, after reading an informative article in DownBeat magazine about the successful formation of the Las Vegas Jazz Society, I gathered a group of jazz enthusiasts in my living room (I’ll never forget that November 17 date because it was the day we brought my newborn daughter home from the hospital – and I suppose that suggests my level of jazz enthusiasm!) to form the Northeast Ohio Jazz Society. For many years thereafter we presented regular jazz concert series in Cleveland, bringing jazz artists to auditoriums at Cleveland State University, Cuyahoga Community College, and clubs around the area. We were also aware of a somewhat similar organization operating in Baltimore, MD – an organization with the rather distinctive name of – not the Baltimore Jazz Society – but the Left Bank Jazz Society, conspicuously named after one of the hipper districts of Paris, France.

The Left Bank Jazz Society was founded simply to promote jazz in Baltimore, by a group of jazz enthusiasts in 1964. The LBJS was founded by a group of men gathered to discuss the plight of jazz in Baltimore; that group notably included Benny Kearse and Vernon L. Welsh (a jazz guitarist on the side); and here it’s important to note that Mr. Kearse, who passed in ’99, was a black man and Mr. Welsh, who passed in ’02, was a white man. I make note of that because the Left Bank Jazz Society history truly speaks to jazz as a social music. Their idea was to form an organization “devoted to perpetuating and permeating an awareness of jazz as an art form through organized activities, such as lectures, concerts, sessions and field trips to festivals and night clubs where jazz is featured” (taken from a LBJS yearbook).

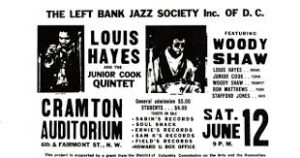

Note that the LBJS was founded in 1964, the same year the Civil Rights Act was passed, and the Left Bank actually grew out of another fairly short-lived group – the Interracial Jazz Society, which as its name clearly implies was not only about promoting jazz but about destroying the racial barriers at Baltimore area clubs and auditoriums. Left Bank’s mission and goals stated that its members must “share a love for contemporary American Jazz Music and a belief in the democratic ideals of freedom and equality, regardless of race, creed or color, which this music exemplifies.” Membership dues were set at $2/year, primarily to cover gig notice mailings; those members were characterized as “subscribing members’; the LBJS governing body was capped at 45 “because that’s all the club room will hold,” according to Mr. Kearse.

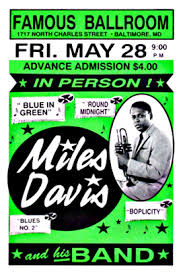

Despite the passing of the Civil Rights Act, the civil rights struggles of African Americans everywhere, including Baltimore, continues to this day. However throughout the course of its existence the Left Bank Jazz Society presentations offered an oasis where folks mixed freely and happily, both on and off the bandstand. Vernon Welsh, who had spent a good deal of his professional life as an auto salesman, spent his last 15 working years managing Baltimore’s Famous Ballroom. Determined to bring great jazz to Baltimore, the Left Bank Jazz Society began its policy of presenting performances with many of the city’s cadre of excellent professional musicians, like the saxophonist Mickey Fields. Other frequent Baltimore-based jazz performers who played early LBJS presentations included the bassist David Baily, the pianist Tom Baldwin, and the drummer Teddy Hawke, who became a sort of LBJS house rhythm section in the classic jazz club tradition.

The earliest LBJS presentations happened at a place called the Al Ho Club in South Baltimore, and The Madison Club in East Baltimore. In 1966 the Left Bank Jazz Society found its permanent home at the Famous Ballroom, in the 1700 block of North Charles Street. Thereafter their mailings announcing presentations included the motto “See ‘ya at the Famous.” In addition to the concerts LBJS also fostered the LBJS Jazzline, a taped telephone message service listing their coming attractions. LBJS also began sponsoring a weekly radio show on WBJC-FM on Saturday evenings, hosted by Vernon Welsh. Other activities included a jazz lecture series at MD colleges and other institutions, fund-raising concerts, and free summer concerts.

The great majority of Left Bank Jazz Society shows thereafter followed a standard and successful format: Sunday afternoons, 5:00p.m – 9:00pm. Admission at the beginning was only $3! Refreshments were available, cabaret-style and BYOB was encouraged. Though inexpensive soul food was made available for purchase, many brought their own food and beverage, while LBJS sold set-ups for mixed drinks. A true communal spirit in celebration of jazz was born and encouraged at the Famous. An example of the early LBJS menu: a plate of chittlins’ and hog maws for $2.20 or a plate of ribs for $1.95, with collard greens, potato salad, and string beans available as side dishes for $.40! LBJS audiences were about 70% black and largely middle-aged. An article I read suggested: “The whites are primarily young converts from rock…”

The capacity of the Famous Ballroom was approximately 600 and they packed the place on Sundays – at its high point presenting over 40 performances a year! (by its 10th anniversary LBJS had presented over 450 performances!) – for some of the real greats of jazz music: from Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Dizzy Gillespie and Stan Kenton to John Coltrane, Charles Mingus, Sonny Rollins, Dexter Gordon, and Stan Getz to Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, and Sun Ra! Looking over the incredible roster of those who performed at Left Bank Jazz Society gigs I was very impressed by the breadth of artists and styles. The Left Bank Jazz Society boasts the melancholy distinction of hosting John Coltrane’s final concert performance, on May 7, 1967 – two months before he passed from liver cancer. Obviously Coltrane was laboring heavily with his illness at that point, though his performance was described as Herculean as usual, curiously those on the scene that day remembered how after his first set Coltrane did not retire to his dressing room to continue practicing – per the legend of John Coltrane – instead on this occasion he actually sat on the piano bench between sets wearily greeting his fans!

Here’s how Cathleen Curtis in the book “Lives & Legacies of Baltimore Jazz”, published in 2010, described that last Coltrane concert performance: “The date is May 7, 1967, and the place is the Famous Ballroom on North Charles Street, where no one has any idea that they are witnessing the last live performance of world-renowned saxophonist John Coltrane, who will die of liver cancer in just two months. The audience is an eclectic array of races, ages, and styles; there are professors from the Peabody Conservatory of Music, college students of all colors, members of the militant Black Panther organization, and middle-aged women dressed in their Sunday best. Yet the only tension in the air is the sound of the music, and the only words exchanged during the performance are “shhh,” the audience hushed under the weight of the extreme intensity emanating from the stage. Coltrane, accompanied by the other members of his quintet – Pharoah Sanders, tenor sax, Alice Coltrane, piano, Donald Garrett, bass, and Rashid Ali, drums – begins with “Resolution,” a section from his spiritual suite A Love Supreme. Only at the end of the first set, which lasts only two hours, is the spell broken by the group’s rendition of “My Favorite Things,” as Sanders plays the piccolo against Coltrane’s soprano sax. The ringing brilliance of both instruments enhanced their piercing high notes and rushing arpeggios. The surprise of the afternoon came when Coltrane began to chant against the piccolo, beating his chest. The crowd went wild.” It should be noted that another account of that concert I read suggested that over half the house emptied out after that first set, but I suppose that’s the nature of any performance as intense as late period John Coltrane.

Looking over a chronology of the first few years of LBJS presentations displays a fascinating and logical evolution of talent giving clear indication that the organization’s financial wherewithal was building as its program developed. They started presenting performances on August 16, 1964 at the Alho Club with some of Baltimore’s finest musicians. Throughout that first year they also began presenting some of the DC area’s notable musicians, including saxophonist Buck Hill, guitarist Charles Ables (who later became Shirley Horn’s longtime bass guitarist), and drummer Bertell Knox. By December of that first year – December 12 to be exact – they presented their first major jazz artist when they presented the Dizzy Gillespie Quintet, with James Moody, Kenny Barron, Rudy Collins, and Chris White.

However they didn’t jump headlong into presenting exclusively touring greats. Instead they continued to build their policy with Baltimore and DC artists, with occasional performances by traveling soloists working with Baltimore rhythm sections, such as February 14, 1965 when they presented saxophonist Jimmy Heath and trumpeter Kenny Dorham working with the Baltimore rhythm section of bassist Donald Baily, pianist Jimmy Wells, and drummer Teddy Hawke.

Because of the interracial nature of the audience, which at the beginning and throughout much of its history was pretty much a majority black audience, and the happy atmosphere engendered by the informal cabaret setting – with folks eating, drinking and enjoying each other’s company in the presence of great jazz – that audience became a significant hallmark component of the overall presentation. Word quickly spread among musicians that something hip was happening in Baltimore on those Sunday afternoons. Those audiences were feeding back their joy to the artists; this further encouraged first class performances, and musicians eagerly took those gigs knowing they too would have a good time on those Sunday afternoons. The Left Bank Jazz Society Sundays at the Famous Ballroom flourished even to the point of the LBJS affiliates in DC and notably two MD prison chapters.

There was at least one wedding ceremony performed at one of the Left Bank Jazz Society events at the Famous. The late great tenor saxophonist Clifford Jordan, who performed several LBJS gigs – the first being with Freddie Hubbard on February 28, 1965 – actually got married at the Famous! I recently asked his widow Sandy Jordan how that came about and here’s what she wrote: “Clifford was great at finding the easiest solution to most situations. We had no time, not a whole lot of money and my family is in Balto. Clifford said “this sounds like a job for Left Bank.” He called and asked and they were delighted. He asked Benny who was playing

July 6th, Benny said Carlos [Garnett]…Cliff said great! They gave us 50% off the ticket price for our wedding guests (about 100) if they were able to advertise the wedding, which they did on the Jazzline. My mom made the food and drink. We were in a roped off area and there were about 500 people including us. Big Fun and Little Money and Big Press. Everyone was happy all around. So we got married on the intermission.”

A significant sight at all of the Famous Ballroom LBJS presentations was seeing Vernon Welsh with his back to the audience, headphones strapped on, working a reel-to-reel tape recorder to capture all Left Bank Jazz Society concert performances. Obviously being out in the open and conspicuous as he was, these were not surreptitious recordings; clearly the artists had full knowledge that they were being recorded, which is quite remarkable in this age of clearances and the understandable insistence by artists of the sanctity of their intellectual property. Clearly Mr. Welsh was doing this purely out of developing LBJS archives, which was quite a prescient move when you think about it.

Vernon Welsh went on to record more than 800 jazz performances at the Famous Ballroom during the 1960s and ‘70s. For many years those performance recordings were stored at the library of Morgan State University. Record producer Joel Dorn, had made a name for himself as an ace producer at Atlantic Records – producing such records by such greats as Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Yusef Lateef, Hubert Laws, Charles Mingus, Mose Allison, Chick Corea, Hank Crawford, Eddie Harris, Herbie Mann, Milt Jackson and many others. When he left Atlantic Dorn, whose big start in the music came as a jazz deejay at a Philadelphia radio station, began supervising reissues for Rhino Records, then developed his own imprint called 32 Jazz. After that he started a label called Label M.

After writing some liner notes for Dorn’s labels we had become friendly and I remember an excited telephone call I got one day from him in 2000. Seems he had acquired a treasure trove of live recordings from the Left Bank Jazz Society and was setting about releasing some of those recordings. Here’s what Joel wrote about one such recording when he released a Freddie Hubbard & Jimmy Heath concert titled “Live at the Left Bank”: “Y’know, sometimes I babble on about how unbelievable it was in clubs in the old days, the 50s, 60s and 70s! Well, my babblin’ days are over, now I have proof. When you hear what’s on this CD, you’ll know exactly what I’m talkin’ about. Dig what’s goin’ on between the guys and the audience. That was the magic. If you were in the right joint at the right time listening to real guys playing the real thing, it’s something you’ll never forget. The Left Bank’s concerts were the hippest gigs in this country. They became the place where everyone wanted to play, and without a doubt Left Bank was the #1 Jazz Society anywhere.”

Just to give you a sense of being in the room at the Famous Ballroom, experiencing great music for a truly “with it” audience, here’s the aptly titled “Bluesville” from that particular Freddie Hubbard & Jimmy Heath performance, with Wilbur Little on bass – someone they brought with them, picking up resident drums and piano in Bertell Knox and Gus Simms, from June 13, 1965. [PLAY “Bluesville”]

Jimmy Heath recalled that performance this way: “It was an event, and the people knew what was going on. We felt like giving our all in appreciation. Folks would clap or holler out your name in the middle of your solo when they got your message or felt your groove. We always played encores and got standing ovations. I will always remember LBJS. It was like a coming home party each time, even though I was from Philly.”

That quote certainly sums up the “old home week” atmosphere of those Sunday afternoons at the Famous Ballroom. Unfortunately, as we’ve all experienced – all good things must come to an end. In 1985 the Left Bank lost its home base at The Famous Ballroom. They continued booking shows at Pascal’s nightclub, Coppin State University and the Teamsters Union Hall on Erdman Avenue, but somehow the magic was lost. After leaving its home base it became increasingly difficult for the LBJS to maintain its audience. By 2000 attendance had dwindled and things became squeezed; unfortunately that was the last year of Left Bank Jazz Society live programming.