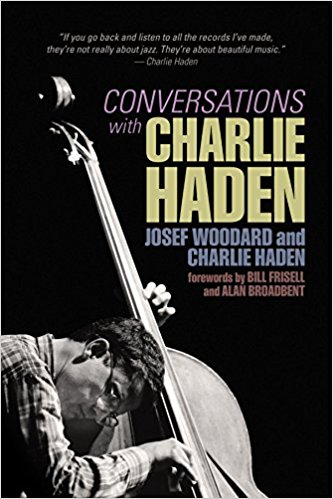

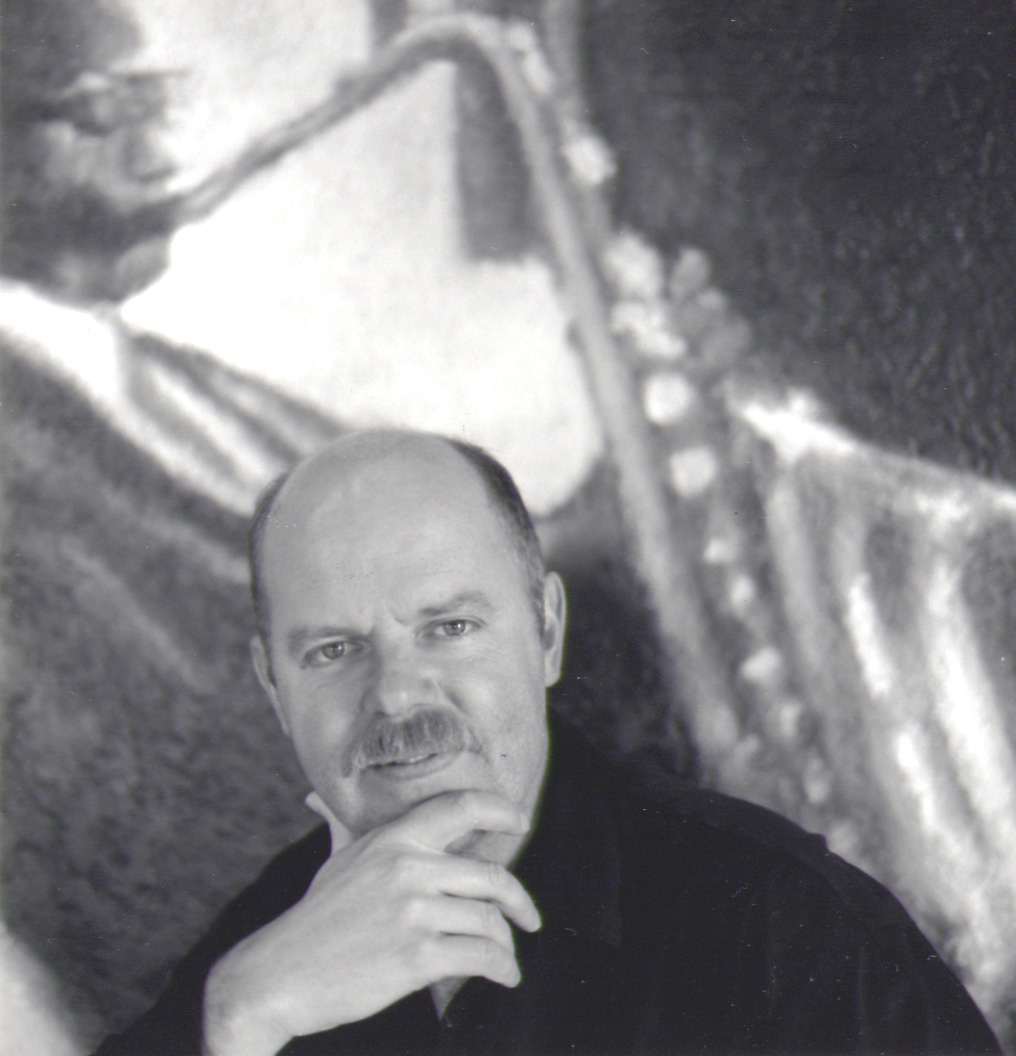

California-based veteran jazz writer Josef Woodard has contributed his prose to a prodigious list of periodicals, including the LA Times, Entertainment Weekly, Rolling Stone, and the usual suspects… DownBeat, JazzTimes, and Jazziz. His current book, released last January, is the very revealing volume “Conversations With Charlie Haden“. One of the most complex, fearlessly and passionately human rights-astute of all jazzmen, the late NEA Jazz Master bassist-bandleader-composer was more than a little candid in his various conversations with Woodard, which span a considerable segment of Haden’s autumnal life in Los Angeles. The book was such a rewarding read we sought out Joe Woodard for some insights into his many encounters with Charlie Haden.

IE: When did you first become interested in learning more about Charlie Haden?

JW: Although my first interview and years-long relationship with Charlie didn’t begin until 1987, I realize that his sound has had a strong impact on me going back to my early days as a young teenager, discovering the power and breadth of jazz and other related musics. His unique voice and presence on those early records by Ornette Coleman, and on the “American quartet” records by Keith Jarrett in the ‘70s grabbed my ear, and not always in an obvious way. His sense of time, his folk-like directness and blend of freedom and solidity had a strong stamp on what he touched, and spoke to my own sensibilities as a music-lover and also a musician.

As I delved deeper into the music, and became a nerdy student of liner notes, album credits, avid concert-going, and family trees of who-played-with-whom-and-when… and why, I grew to have greater respect for Charlie and his distinctive place on the jazz—and indeed, musical–landscape.

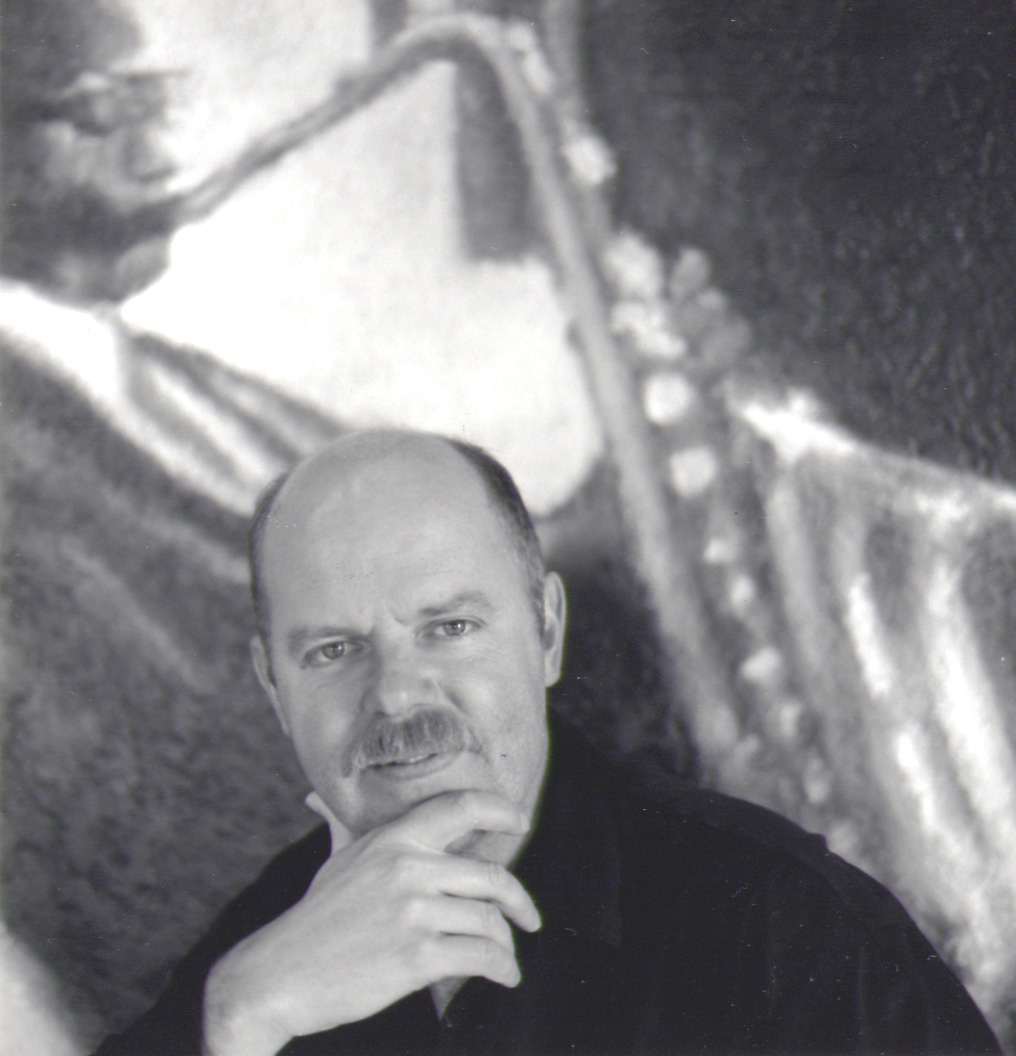

THE INTREPID INTERVIEWER HIMSELF

IE: What was your interview experience with Charlie?

JW: I first encountered Charlie when I was a young-ish music journalist, in my late 20s, and when he was settling more deeply into life in Los Angeles, where he had moved back to be close to his children and to tend to his job as the founder of the CalArts jazz program. I had been writing for music magazines since the early ‘80s, and was just starting to focus more on specifically jazz magazines, pursuing my passion for that world.

I interviewed Charlie at the old At My Place in Santa Monica, where he was launching his new band Quartet West—which would fare well for him for over a quarter century. I was there to write a cover story on him for JazzTimes, my first story for that magazine. We immediately hit it off, I felt. Sometimes, an interviewee keeps a certain distance in an interview situation, which is understandable, but he was very warm to me from the outset—I think especially when he discovered what a long and deep fan I was of his work. I do remember a bit of tension when I expressed my surprise this new band would be a “straighter” endeavor than what I was used to from him, but that also became a point of reference in what was really a transition moment in his career.

After that point, around the age of 50, Charlie’s life as an artist who took charge of his own steady flow of interesting new projects, many under his name or creative guidance, really took off. And, partly because I was a member of the thinly-populated ranks of jazz journalists who actually live in Southern California, I was there to talk with him about many or most of these projects for the next twenty years. I think it was clear to him that I was particularly thrilled and plugged-in to his life with his greatest band, the Liberation Music Orchestra, and also plying him with yet more questions about Ornette, the man, the myth, the musical visionary. Charlie was happy to oblige.

IE: As opposed to the usual book of interviews, the title of this book is certainly an accurate reflection of its tone; over time these are indeed more conversations than interviews. Does that reflect an evolution of your relationship with Charlie, or was it pretty much always that way?

JW: This was my second book for Silman-James Press (well, third, after a book on the Montgomery Brothers, which is still on the shelf, but hopefully will see the light of day at some point). After the arduous process of writing my book on Charles Lloyd, which took seven years, I couldn’t really see going that exhaustive route again with Charlie Haden. As I went through my trove of interviews with him, and discovered more lurking on hard drives and in piles of interview tapes (cassette mode), I realized that our interviews really did have a more conversational quality than many of the interviews I’d done, borne of the easy rapport we had.

After discussing it with my editor, I decided to go for the “Conversations with Charlie Haden” approach and title, and keep the book in a fairly straight, chronological and academic format, with my own introduction and minimal intrusions on the back and forth between us. To my surprise, I thought the format worked nicely, and Charlie managed to cover the spread of his amazing, meandering and mercurial life over the course of those interviews/conversations.

IE: One year I had Charlie do a residency at the Tri-C JazzFest (Cleveland) where he played two concerts: Quartet West with Joe Lovano subbing for Ernie Watts, and a Liberation Music Orchestra concert with an exceptional group of Cleveland musicians under the direction of the saxophonist-educator Howie Smith; Charlie was extremely delighted with both evenings, particularly with how the musicians played his Liberation Music Orchestra selections. My wife still recalls times when Charlie called the house looking for me, she’d answer and hear “hey man, this is Charlie, is Willard there?” I’d imagine you were the recipient of such calls considering your many conversations. What were some of your more memorable personal moments with Charlie and Charlie Haden stories?

JW: I know exactly what you’re talking about, concerning Charlie’s social ease and flow. He lacked pretension and was happy to converse on matters of music, politics, the news of the day, or the history of his musical life going back to when he was a two-year old radio star, singing on his family’s influential Midwestern radio show. I think he would avoid idle chatter, but was happy to befriend true music fans and musicians far and wide—and from many cultures.

Personally, he would call up, outside of our official interview sessions, and want to share some new news, or ask if I had any pull with NARAS (he was fairly obsessed with the Grammy Awards, seeking to be represented for his work, especially once he started his Haden-led career chapter in earnest). I think he liked the fact that I was also born in Iowa (though have lived in Santa Barbara, California since I was one) and that I was a musician with a record label and was always working on some musical project or another.

“Hey, man,” he said more than once, “how’s your band Headless Horseman?” I kept correcting him: “thanks for asking. Actually, it’s called Headless Household.” And he’d say “oh, man. That reminds me: people always call my album Haunted Heart Haunted House,” with that classic, Haden-esque belly laugh.

I highlighted one passage in the book that really strikes to the essence of Charlie Haden’s diverse interests: (pg 225) “Whether it’s tango or bolero or fado or whatever it happens to be, I try to do it, and I’m not happy until I do everything that I’ve been thinking about.” I’d have to say Charlie Haden never half did anything. Is that an apt summation of the man?

That quote does get to the heart of what made Charlie such a unique and can-do figure in jazz, and music at large. He would just follow his heart into areas he might not know much about, at first, but his infectious passion drew musicians and record company execs, festival heads and other facilitators into his machinery in the making. He fit beautifully into the contexts of fado, with Carlos Paredes, and boleros with Gonzalo Rubalcaba, and assorted genres folded into the wonder of his Liberation Music Orchestra projects—with the generous help of his great arranger-allie Carla Bley. And he had some truly magical piano-bass encounters during his lifetime, with Jarrett, Kenny Barron, and Hank Jones, to name just a few.

Ironically, one album which some thought was another stretch for him—his fantastic old school country project Rambling Boy, from 2008—was, in fact, a return to some very deep roots, going back to his family’s radio show in Iowa and Missouri. Ironically, again, that album—an amazing live show of which I caught at Disney Hall in Los Angeles—was also one of his best-selling albums. So much for genre-tagging, especially for an open-eared, open-hearted artist like Charlie Haden.

IE: If someone were new to Charlie Haden, what would you recommend they listen to in order to get the essence of the man?

JW: He has such a vast discography, as a sideman and under his own name—as well as with his bands Quartet West and the great Liberation Music Orchestra, it’s hard to whittle down to an essential list. To come up with a Top Ten—at least from what strikes me as the essential core of who he is—is a subjective thing. These are projects in which he was clearly the conceptualist and leader, but listening to his work on the early Ornette Coleman records or any to the ‘70s work with Keith Jarrett and Old and New Dreams are important.

Here goes:

Liberation Music Orchestra (Impulse!), 1969

Folk Songs, with Jan Garbarek and Egberto Gismonti (ECM), 1979

Liberation Music Orchestra, Ballad of the Fallen (ECM), 1982

Quartet West, Haunted Heart (Verve), 1991

Haden with Hank Jones, Steal Away (Verve), 1995

Haden and Pat Metheny, Beyond the Missouri Sky (Nonesuch), 1997

Haden with Gonzalo Rubalcaba, Nocturne (Verve), 2001

Liberation Music Orchestra, Not in Our Name (Verve), 2005

Rambling Boy (EmArcy), 2008

Haden with Keith Jarrett, Last Dance (ECM), 2014