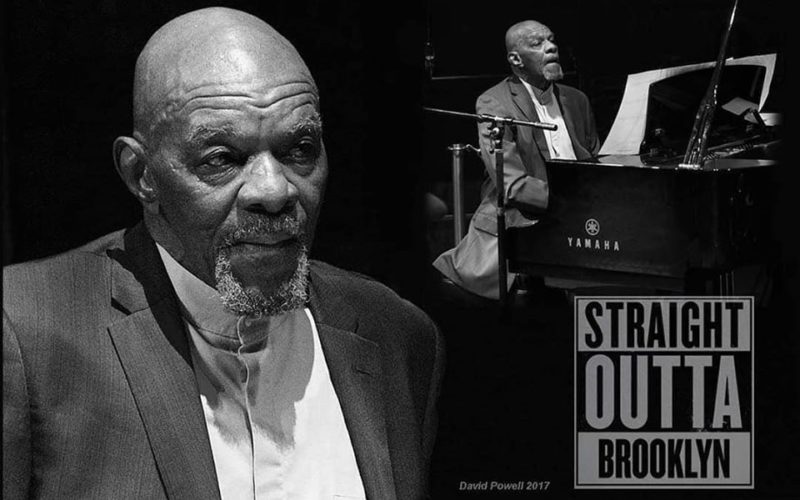

R.I.P.—Brooklyn born jazz giant, pianist Ed Stoute moved on from our plane of existence to join musicians in a heaven ripe for listening to his talented fingers. Stoute traveled the world with the flavor of Brooklyn’s Bebop, with jazz standards infused with tributes to the best compositions of Monk, Miles, and Coltrane.

R.I.P.—Brooklyn born jazz giant, pianist Ed Stoute moved on from our plane of existence to join musicians in a heaven ripe for listening to his talented fingers. Stoute traveled the world with the flavor of Brooklyn’s Bebop, with jazz standards infused with tributes to the best compositions of Monk, Miles, and Coltrane.

Ed Stoute has been playing African American Classical Music, also known as Jazz, for more than 60 years. Composing more than 100 tunes and arranging standards with a repertoire ranging from Bebop to Brazilian styles. Brooklyn’s “Jazz Ambassador” carried on a music tradition that has a rich history in Brooklyn. Performing with his ensembles in large and small venues, few brought him as much joy as Fort Greene’s “JAZZ966.” Here, Ed plays on in the hearts and memories of his contemporaries and in the souls and imaginations of the young musicians he inspired.

(Remembrance from the Central Brooklyn Jazz Consortium)

Edwin Stoute: Yes I am, actually this part of Brooklyn – Bed-Stuy – on the other end, on Thompkins Avenue. This (MacDonough Avenue) was the sidity end [laughs]. Where I grew up was the slums. I went to East New York Vocational High School; I quit high school in the last year, ran off to play music, and when I was about 30 I said ‘let me go back and finish that diploma.’ So I went off to Brooklyn Tech and [finished].

When you were growing up in Brooklyn did you have any interest in jazz music?

Oh yeah. When I was growing up my oldest sister got piano lessons and my oldest brother go violin lessons. My bed was in the living room where the piano was, I was four years old. On Saturdays this big German man would come and give my sister a piano lesson, and she didn’t want to play the piano, she couldn’t get away from there fast enough. [But] I was fascinated with this thing [piano], this thing that makes this sound just fascinated me. The minute she was gone I was there diddling around. I couldn’t get away from that piano.

So when did you start taking lessons?

I started taking lessons when I was about 19; I was actually self-taught, in the union, doing gigs… couldn’t read a note!

At what point were you capable of playing a gig?

I was doing gigs from the age of 18, I couldn’t read a note but my ears were always big, so I was able to do calypso gigs, little dances and stuff like that.

So from the time you were four years old you were figuring out the piano on your own?

I started figuring it out by myself. I knew but I didn’t know; like your ears tell you something is the right thing but you don’t know the theory behind it so you really can’t expand on things.

Were you interested in jazz as you were developing yourself as a piano player?

When I was real young I was actually interested in the classical side and at that point I would make up tunes, compose tunes. I couldn’t read the music to play the things my sister would play, so I used to make up my own melodies and figure out ways to play them; that’s actually served me well because I’ve always composed music. I stayed on that direction, so I’ve always been a composer of music – I haven’t made any money at [composing] but I plan to; everybody always likes what I write.

How did you develop your interest in jazz?

That happened when I was about 14 or so, my two older sisters had their boyfriends and they came into the house with these jazz records and I started hearing this music. They played Stan Kenton, some Bird, some Bud [Powell]… So I heard this and went in that direction.

When you say you went in that direction, what did you do?

When I heard Bud Powell… that was it! Bud Powell turned everybody around, especially at that time he was on fire. I was trying to play all that, I didn’t know what I was doing but I was agile, my hands were agile. We used to have little jam sessions around the corner at a friend of mine’s house and the drums were my friend’s older brother had been to the war, he had one of those big shells and made it into a lamp; that lamp became the cymbals for the drum. It turned out the drawer was the drum. We were fortunate because on that block Kenny Dorham used to hang out, on Hancock Street between Thompkins and Marcy. He actually came in the house one day and played for us, we had guys that did that, older guys who would stop in now and then, they knew we were trying to play. We were very fortunate.

What other professional musicians were you aware of around your neighborhood?

There were a lot of them: Ernie Henry, Cecil Payne, Matthew Gee… there were a lot of guys… There was a guy named Maurice Brown who played drums. There was a guy we called Little Diz, Webster Young, he was around in Brooklyn then and he used to come and hang out with us.

So there were a lot of jazz musicians around the neighborhood?

Yeah, and they’d hear us trying to play and they’d come and hang with us.

What about clubs or bars in your neighborhood, were there any around when you were coming up?

You had so many places it was ridiculous. There was the Continental over on Nostrand Avenue, a placed called the Tip Top – what they played in there wasn’t always jazz, but they had shows: you’d have a comedian, a singer, a band, an MC. The Tip Top was on Fulton Street, right where Boys & Girls High School is now. And there was a club called the Berry Brothers that had music off and on, that was on Fulton Street in the same area. One of the big clubs was the Moulin Rouge, which was on Putnam and Sumner Avenue, which is now called Marcus Garvey Blvd; the place [building] is still there but it’s something else.

What went on at the Moulin Rouge?

Everybody played in there, including Miles Davis; Walter Bishop, Red Garland I remember… This was a place that had a long bar and back of the bar was a long bandstand; they had a white grand piano in there. The places were kept in fairly good shape, especially the places that were jazz clubs. The Moulin Rouge was a good place.

How old were you when you started frequenting these places?

We were frequenting these places from the time we were old enough to get in… 18. We all loved jazz so we used to follow jazz everywhere. I remember me and some of my friends got jobs working for Ruben H. Donnelly as stock boys and what was great about this job was in the wintertime they had you working, but when the springtime came they laid you off – but it was known they were going to hire you back in the fall. So summertime when we were living with our parents we’d get the unemployment checks and we were hanging out at all the clubs, catching all of the music. Thelonious Monk… that’s when they had the cabaret card business and we caught Thelonious Monk playing on Fulton Street at the Elks Club playing a dance because he couldn’t go into a lot of the other venues, and you’d catch him playing places like that. But wherever anybody was, we were there – we hung out, middle of the week, we didn’t care. The Continental on Nostrand Avenue… the Blue Coronet wasn’t happening then, but the Continental was the place then. Turbo Village on Reed and Halsey Street… Freddie Hubbard used to be there playing the Turbo Village when he first [came to New York].

Take a place like the Moulin Rouge… what would an evening be like there?

It was a fantastic evening because they had all of the good jazz groups in there every week.

What time would they start and how many sets would they play a night?

About 9:00 and it was a lotta sets; gigs were 6 hour gigs [back then], so probably 9pm-3am, at least 4 or 5 sets. I remember when I started playing a gig was 6 hours.

Were these the kind of places – the Tip Top, Turbo Village, Moulin Rouge… were these places where you could go into the place, pay a cover charge, and buy a drink and stay all night?

The Moulin Rouge I don’t think even had a cover charge; you could go in there, nurse a beer and stay all night. Sometimes, if we had a little more money we didn’t mind buying a couple of things, but I didn’t drink at that time. There was a place called the KC Lounge, on Gates & Throop, it was an organ room; there were certain rooms that were organ rooms. You had the Baby Grand on Fulton and Nostrand, which was owned by the same people that owned the Baby Grand in Harlem. As a matter of fact one of my first gigs, where I first learned to play for singers, I started working at the Baby Grand in 1960 or so. All we wanted to play was bebop – we were young, we didn’t want to play for no singers! So I got this gig at the Baby Grand with bass and drums. The set-up was they had a comic MC and a shake dancer; the girls didn’t take off all their clothes, they just did a little dance and took some clothes off, and that was quite sufficient for the times [laughs]. They usually had a singer in the rock or blues style, and they’d have one singer who was a jazz singer. That’s what the show was composed of, it was a variety show.

Was it that way at the other clubs?

Not so, the other clubs were strictly jazz, like the Continental was jazz; I believe the Turbo Village was mostly jazz. Places like the KC Lounge, that was organ, blues and that kind of stuff, the organ trios. The Moulin Rouge was strictly jazz,

You began playing professionally at age 18. Did you play any of these clubs?

I played at the Moulin Rouge, but not at the other clubs, and it was later on that I played at the Baby Grand; I got drafted and went into the service and came out at the age of 25, so it was around then that I played at the Baby Grand.

When you played at the Baby Grand, who did you play with?

I played with a guy named Jimmy Chisholm, a good tenor player, and we played for the shows.

So you backed up the jazz singer, the R&B singer…

…And the comedian, and the shake dancer…

So what kind of music did you play in all these situations?

It depends; for the shake dancer you had to play something Latin-flavored for them, but you had these rock singers who came in and they had their music, but most of them didn’t have music. When a new show was coming in we had to get there early Friday night to rehearse. And most of the time there wasn’t really any music, we just did the show. One problem with that is on Monday nights we had to go to the Baby Grand in Harlem because the regular band was off that night and we had to play that show totally cold. The guy that ran that show then was Nipsey Russell, he was a nasty sucker, I didn’t like him. We had this show, we didn’t have a chance to look at the music and rehearse it, just look at it and try to play it. So if you made a mistake he’d talk about people like a dog and I don’t appreciate that.

When you played at the Baby Grand, when would the week start?

Friday night. When a new show came in we were playing six nights a week. We’d play Friday, Saturday and Sunday, Monday nights in Harlem, Tuesdays we were off, Wednesdays we were back playing in Brooklyn. They had a singer’s jam session on Wednesday nights and we had to deal with that. All of the singers – real amateur singers – they all wanted to sing the same tunes that were popular at the time, rock stuff, “Stand By Me”, those kind of things [laughs]. So it would be one singer after another, some of them were so amateur they would change key in the middle of the tune, so we had to follow them around from key to key.

What kind of gig would it be at the Moulin Rouge?

That was a good gig that was a strictly jazz gig. At one time it was my band, other times it was somebody else’s band. A guy I started playing with was Harold Cumberbatch; his daughter [Tulivu Donna Cumberbatch] is a singer now. He played baritone and he hired me to do some gigs with him. As a matter of fact that brings up some different places. There was a place called Ben’s, on Lexington and Sumner [Marcus Garvey Blvd.] Ben’s was a joint that had a raggedy upright piano, and I played there with [Harold Cumberbatch]. And there was a place called Paul’s, on DeKalb Avenue right off of Sumner Avenue [Marcus Garvey]. Paul’s was a nice place; I got a couple of gigs there with Harold, who had a fairly decent name. His favorite tune was “Stella By Starlight” and he named his horn Stella. Harold was a funny cat.

So who else would you play with during these times?

There was an alto player around named Buddy Williams, he was burgeoning and budding. In fact there was one night I played with him and all of a sudden… you ever hear someone when they’ve just completely got it together? This guy was so beautiful, he played so much. Buddy had just gotten there and it was only a couple of months later he got hit by a car and killed… going to his day job. He played alto and he had such a warm sound.

Did you ever work a day job?

I worked day jobs on and off. I worked for Ruben H. Donnally going up to Mt. Vernon loading mail trucks with 90lb mailbags… I worked all kind of jobs around there. I’d go for a job sometime and these places would look at me and say ‘oh yeah, big black guy, got a job on the platform for you.’

This was also back in the days when soloists would travel the country and pick up local rhythm sections, like Sonny Stitt. Did you ever do any of that?

No, I never did any of that. I once had an opportunity to play with Stitt, but I didn’t do it, at the Blue Coronet. I shoulda just done it because Stitt was a great guy. He was the kind of guy who would see a young cat in the club with his saxophone between sets and say ‘hey, come on up here.’ You weren’t gonna walk in that club with no horn and don’t play. He’d bring you up there and let you play; I mean you know you’re gonna get carved [laughs], but I think that was a great opportunity. He was the kind of guy who was trying to give you an opportunity to come up and be heard.

Did you find a lot of that kind of attitude among the musicians of that time?

A lotta that, a lot of compassion in a different way too because a lot of the older guys were junkies, and we loved them – we loved their music too. When we were still in high school those dudes used to be begging us for change, to get their fix. We’d give them quarters, dimes and nickels and whatnot. But there’s something that all of them said, they said ‘listen, whatever you see us do don’t do it, it don’t do you no good.’ They used to tell us , ‘stay away from this.’ That [warning] served me well. I got into a little bit of mild trouble, but I never stuck no needle in my arm. I remember once I saw a guy stick a needle in his arm, draw some blood and shoot those drugs then fall asleep. Another guy came right behind him, took that needle out of his arm, ejected the blood and shot himself up! I said to myself, these guys gotta be crazy! That’s how AIDS took over.

Take me up through the time when you started developing yourself as a musician in your 20s.

When I really started developing was when I came out of the Army at 25 and got this gig at the Baby Grand. I was real young, never played for singers before, didn’t know a lot of tunes. So every time a new show came in there I was under pressure, I’d have to see what tunes they were going to play and pray that I could get it together because there were some tunes I’d have to go get the book and learn. I was under a lot of pressure but also at the time there was a school called Hartnett Music Studios, it was in Times Square, upstairs, and that’s where everything really came together for me. Because I was still playing a lot by ear, I didn’t know a lot about different chords and structures and how to change them up, but when I went there [Hartnett] every day was a revelation because I was studying composition and arranging and they started teaching you little things about voice leading when you’re writing for different horns to try to make everybody’s part mean something, to make it move… that’s voice leading.

With what I was already doing, when I went there [Hartnett] they’re explaining it and opening it up, and showing me how to expand on things; it was a fantastic time! Even though I was tired because I was working at the Baby Grand and getting home at 3:30 in the morning and getting to music school at 9:00, not getting much sleep so I was tired. But [Hartnett] was so interesting it didn’t make much difference. You can’t be but so tired when you’re dealing with something like that. I learned a lot about music in the couple of years I went there, it opened me right up.

How long did that gig last playing those shows at the Baby Grand?

A couple of years. It was good experience because I learned to play with singers.

Who were some of the singers you played for at the Baby Grand? Did any well-known singers play there at the time?

Not there. Later on I played for Dakota Staton a couple of times, I played with Betty Roche, but not at the Baby Grand. I got a gig at Wells [in Harlem], my first-ever trio gig, with Joe “Bebop” Carroll. Remember Joe Carroll? “The Land of Oo-Bla-Dee” and all that stuff… That was my first time playing with a trio that was a whole different experience. So what happened was the gig was a singer’s gig but Joe was singing bebop so it was nice. The first two weeks [of the Wells’ gig] was Joe Carroll, the second two weeks was Betty Roche.

Did you play with these singers in Brooklyn as well?

No, just at Wells. But I played with Joe Carroll at a few other places, but that was the only gig I did with Betty Roche. She was a beautiful person; as young as we were she loved us because of the way we dressed. We dressed sharp & clean. It was myself and Bob Cunningham, Bob had just come to Brooklyn and that was his first gig. That was the time when you dressed sharp. Cats nowadays get on the bandstand with jeans and what not… forget that, no no. That, I don’t think, should ever happen. I think you do have a duty sometimes to spruce up a little bit.

So what’s the importance of being well dressed on the bandstand?

I feel like how can people look up to you if you come in the place looking like a bum. A lot of people are just there for the music and they don’t care, but there are people that do [care]. If people out in the crowd are dressed better than you, I think that means something. There are some gigs where you don’t really dress up and that’s fine. But the Brooklyn Academy of Music on Sunday evening… I think you put a suit on at least.

Do you think the audience takes musicians more seriously if they’re dressed well?

I think sometimes, but I don’t think that’s the only thing that’s necessary… you gotta be able to play, that’s first and foremost. But being dressed decently, I think that helps, that makes a certain kind of impression.

So what did you do when the gig at the Baby Grand ended?

Muddled around a lot. After that I started playing with Illinois Jacquet, he had a quartet and we would do gigs a lot in Boston and Toronto; we went to Houston one time but mostly it was Boston and Toronto. We went to Chicago and Cleveland. We might be out seven weeks just between Boston and Toronto. There was a place in Toronto called the Town Tavern, and there were two different places in Boston – Lenny’s-On-The-Turnpike was a little joint in Boston.

After your gig at the Baby Grand did you get many opportunities to play around Brooklyn?

I played a lot in Brooklyn. I played a lot of little dances and stuff like that, not real jazz gigs. Sometimes it was the Moulin Rouge. But most of the gigs we played were like commercial things – weddings, that kinda stuff.

Did you get many opportunities to record?

No, I recorded once with Jacquet – as a matter of fact on an album I wrote one of the tunes and he turned me around; they didn’t allow me to play on my own tune; that really turned me around because I had all these ideas about how things should be, but they’re [record company] into their commercial thing. They had this sister play [piano] on the album because ‘she’s more funky’, that’s [producer] Esmond Edwards out of Chess, Checker and Argo Records out of Chicago. When you have certain people that are controlling the music and they have no respect or no feel for anybody, they’re just doing what they think is best because they’re controlling the money, so that’s what happened.

So what other kinds of situations did you work in Brooklyn?

Like I said, it was a lot of weddings; there weren’t a whole lot of good paying gigs.

Did you work at the Blue Coronet?

I worked at the Blue Coronet. I played with Carlos Garnett – he was a Brooklyn boy then. And I did a gig there with my own group; we did a gig with a quintet and a singer, a girl called Gwen Michaels, she was a good jazz singer. We did some of my own music but I never got a chance to go too far with it because the world is just not wide-open like that and I wasn’t as well-known as I needed to get, and I was working in the day. And when you’re working in the day you can’t travel, you can’t get into the real circle of things, you can’t hang out.

Were there ever any opportunities to travel?

There were some, but I had to turn them down. I’d get a phone call, somebody got my name from somebody and they’ve got a gig in Ohio or wherever and I had to turn it down.

That scene that you described in Brooklyn: the Moulin Rouge, the Continental, the Tip Top, Berry Brothers, Turbo Village, and later on the Blue Coronet… How long did that scene last?

That scene lasted from the 60s into the early 70s; everything seemed to break down after we got through the early 70s.

What do you think caused that breakdown?

You know I’m not really sure, but all of a sudden there were fewer and fewer jazz clubs. They had some beautiful places that opened up. There was a place called The Id that opened up in the 70s, it’s now a church on the corner of East New York Ave. and Utica Ave. It was a huge place; it was originally Satellite Caterers and they called it The Id, and it was a beautiful place with a big long bar, real nice place. I’d walk in there and Cedar Walton and them would be playing, Billy Higgins would be laughing at me while he’s playing… They had some hellified groups in there – Charles Davis, Richard Davis…

Why do you think the need for these clubs diminished?

I don’t think the need diminished, I just think there were financial difficulties and stuff and places started to close. All of a sudden that place they called The Id – Satellite Caterers – closed, and that place was hot, the music was HOT in there. The Continental went [out of business] way before; the Blue Coronet was just the Coronet at first… We had jazz at the Brevoort Theatre, on Bedford Avenue and they had jazz sometimes… I played in there. There were just small groups in there. The group that I caught playing in the Brevoort was Miles Davis’ group, the one with John Coltrane, Cannonball Adderley, and Wynton Kelly; they played there for a complete weekend – on Bedford and Brevoort Avenue, one block past Euclid Pl.

Would the movie play before or after the music?

They didn’t have a movie there at all, not when they booked Miles Davis because Miles Davis was expensive. There was a place on Utica Avenue near Park Place called The Fantasy where some top groups, some trios played; Wynton Kelly might be playing in there… That lasted a good while and I played there towards the end of it.

There was a place called The Centaur on Franklin Avenue between Prospect and Park, a lot of people don’t remember The Centaur but Wynton Kelly lived pretty much around the corner and whenever the Wynton Kelly Trio was not playing with Miles you could catch them at The Centaur every weekend; Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers and Jimmy Cobb. There was a grand piano up behind the bar. If they had recorded what Wynton Kelly played in there it would have run around the world like a shot, that was one of the most dynamic trios I’ve ever heard. With Wynton Kelly everything is going to start swinging immediately! And every chorus it would go to another level, until they got you in your chest and you would say ‘they can’t swing no more than this!’ They got your chest tightening up – and the next chorus, another level… That’s the way they played. That was an awesome trio.

At these places was the clientele strictly black?

Mostly, yeah; that was a black neighborhood and you didn’t find too many white people coming down there. The people that came down there came to hear some music, it was a nice group, and everything was beautiful. This was a place designed to hear music.

Were these clubs you’ve talked about all like that, where people actually came to hear the music and the music was not ‘incidental’?

Most of the clubs people came to hear the music, at that time. They had music in all kinds of places; up along Fulton Street they had a place called the Verona Café. Before you got to Nostrand Avenue there was a place called the Carroll Bar and Lucky Emmett, who was a tenor player, he’d be playing in there. He had a great pianist named James Sykes – they liked to drink too much, the both of them, but heckified players. A horn player would come in there wanting to sit in and he’d say OK. Guy would call “Cherokee” and they’d give the intro and you’d see the horn player get up there trying to play the melody with Lucky and you’d hear [the guest tenor player] scuffling and you’d wonder why he’s scuffling, that was because they played “Cherokee” a mile a minute in B-natural instead of B-flat. So this guy goes up there thinking he’s gonna play in this comfortable key when all of a sudden he scuffles a while then go sit his ass down [laughs].

So what are you doing these days?

These days I work with the Harlem Renaissance Jazz Orchestra, a big band. I’ve been working with them for a few years and we’ve done some things in the park, we’ve done some Jazzmobiles, and every July we close the session at Lincoln Center Outdoors – the Mid Summer Night’s Swing, where they have the bands come out for people to dance.

These places you played in Brooklyn were you playing for dancers or were you playing for listeners?

Sometimes we played for dancers, a lotta times. It could be Hancock Hall, and at one time there was a Sonya Ballroom [currently Akbar Hall]. We used to play a lot of dances at Shadow Gardens [Manhattan], down on the Bowery – a big venue that had a lot of different halls and there were some guys who used to rent out the whole hall and put a different band in every room. That was a busy spot.

Do you ever play the Jazz 966 concerts [Friday evenings at 966 Fulton Street]?

I play 966 usually once a year with my group, and I play my original music. It’s a good audience, they all know me; I used to go in there with a trio and a singer, but I got to the point where I was writing a lot so what I did was I changed everything and formed a quintet in 2005 and now I’ve been going into places with the quintet: Julian Pressley on alto, Keith Loftus on tenor, David Jackson on bass, Butch Bateman on drums and myself. Sometimes when Keith can’t make it I use Gene Gee on tenor. We rehearse at Donald Sangster’s house.