Among the many travels I was afforded while working with NEA Jazz Master pianist-composer-bandleader Randy Weston (African Rhythms, 2010 Duke University Press) was an extremely pleasant journey to Annecy, France, a lovely alpine town hard by Lake Annecy and the Swiss border where Randy had resided for a time. It was on that trip that I also met the man who had produced several of Randy’s late career records for the Universal Music Group, Jean-Phillipe Allard. More recently Jean-Phillipe has launched his own Artworks imprint. What exactly is the role of a record producer and how does one arrive at that particular station in the world of recorded sound? Recently we posed questions to Jean-Phillipe about his record business odyssey and about his plans for the Artworks label.

- How and when did your career in the record business evolve to record production

In 1987 I was hired by PolyGram France to create a jazz department. It was also therise of the CD format and there were a lot of reissue activity, as well as,the reactivation of PolyGram/Verve/EmArcy jazz A&R, first in Japan with the great producer/journalist Kiyoshi Koyama, then in the US with the signings of the Harper Brothers, Betty Carter, Sphere, Charlie Haden Quartet West. Initially, my job was supposed to only be the marketing of international (signed outside of France) jazz product and the reissuing of French jazz repertoire (Django Reinhardt, Stephane Grappelli, Miles Davis, Chet Baker …etc).

Kiyoshi Koyama contacted me in 1988 to help him to produce a recording of John Lewis in Paris with the French all-stars, Christian Escoudé, Pierre Michelot, Michel Gaudry and Daniel Humair. The recording happened in December 1988, and it was my first time in a recording studio. This is clearly when I first contracted the jazz producing and recording bug! Directly witnessing the creation of music that did not exist the minute before and will never be repeated, but immortalized on tape, was an unforgettable thrill. Koyama became my first mentor, John Lewis and Pierre Michelot became lifelong great friends and teachers. Christian Escoudé, who is still active and on the scene, is also still a close friend.

About the same time the French arranger/big band leader Laurent Cugny sent me a recording of his orchestra playing the music of Gil Evans with Gil himself. It became my first signing, and right after that Jacques Muyal, an old friend of Randy Weston, contacted me about a new project with him. Randy, who was a little forgotten at that time, was one my heroes. I deeply loved his music. At the same time Christian Escoudé came with a project of “Gypsy Waltzes“ mixing the tradition of gypsy jazz, bebop and traditional French music. I recorded Christian’s project in May 1988 and Randy’s Portraits tryptic in June 1988. These 3 projects launched me into the world of producing and executive producing new projects. Randy became a very good friend and we then worked on a lot of his projects and stayed in touch until the end of his glorious life. He was also very important in teaching me the history and the spirit of this music. After these projects everything happened naturally.

2) Talk about your must rewarding experiences as a record producer.

All the recordings with Randy or with Abbey Lincoln were very special but the recording of Randy’s “The Spirit of Our Ancestors” that I coproduced with Brian Bacchus was certainly a highlight. We had in the studio Pharoah Sanders, Billy Harper, Dewey Redman, Alex Blake and Jamil Nasser, Idris Muhammad, Talib Kibwe, Dizzy Gillespie, Idrees Sulieman, Benny Powell, Big Black, Azzedine Weston and Her Greatness Melba Liston. Except for Brian and myself, everybody was a legend. The spirits was so powerful, and we had the feeling that history was being made. I still have goose bumps when I think to some of the amazing moments from this session.

In 1991, Abbey asked me to record with Stan Getz and we put together the recording of You Gotta Pay the Band. That session altogether took 5 hours over 2 days as Stan was struggling with his health at that time, so we had short days. It was an easy and spontaneous session. Hank Jones, Mark Johnson and Charlie Haden were relaxed and Inspired. Abbey, as always, was intense, deep, real and impressive. She gave inspiration to the musicians including Stan who was very touched by her soulful singing and moved by her lyrics. It was a dream session.

The other highlight with Abbey was the recording of Abbey sings Abbey that I coproduced with the great engineer/producer Jay Newland. I selected, with Abbey, 12 of her own songs. At that time Abbey was not in great shape, so we had only 2 hours per day to record her. These 2 hours were so heavy andemotionally charged that it was indescribable. Abbey was literally singing for eternity. Everybody who participated in this session still talks about it as one the best things they ever did. It was pure magic. It happened to be her last recording. People Time, the duet album of Stan Getz and Kenny Barron was also Stan’s last recording. Stan wanted to do it at the Montmartre Club in Copenhagen because he knew that Kenny loved the piano there. This one was another “spiritual” experience. Stan had only 3 months to live and even if sometimes he was getting tired, he was playing better than ever. He had this special relationship with Kenny, and they had this kind of telepathic connection. I never saw them talking about the repertoire or the keys or anything else; they were just playing and inspiring each other to the highest level. I was so lucky that Stan asked me to produce this recording. Since then, I worked and still work with maestro Kenny Barron. I was very moved by this recording and was quite aware that this kind of experience may only happen once in your life.

Another unforgettable session was with the South African genius, Bheki Mseleku. My friend, partner and coproducer Brian Bacchus turned me on to Bheki when he emerged from the British scene. We decided to produce his first American project with the musicians he was dreaming of working with. The lineup again was historic. We had Pharoah Sanders, Joe Henderson, Abbey Lincoln, Marvin ‘Smitty’ Smith, Michel Bowie, Elvin Jones and Rodney Kendrick among others. Bheki did not read or write music, but his compositions were extremely sophisticated and despite 2 fingers missing on his right hand, his amazing virtuosity on the piano was stunning. He was also singing and playing the saxophone extremely well. He really seemed to be coming from another planet. At the time of this recording, apartheid was still going on in his country and that too was another planet. Again, the spirits were powerful, and this session stays very special, inspiring and unique to me.

3) For some the role of a record producer is not easily defined. Tell us what you see as the responsibilities of a record producer.

The role of a record producer for jazz depends a lot on the artist and also the producer. Most generally the producer is in charge of the preparation of the session, choosing the right studio, the right engineer, the rehearsal studio, the piano, the piano tuner etc… Of course, the artistic aspect is very important.

With Abbey Lincoln, she was writing or choosing her material, then we would talk and try to define the kind of production she would like for each song, then I would suggest musicians and arrangers. The final decision was always mutual. During the session we would choose the takes together. Then I would supervise the mixing and ask her for her approval or changes. Same thing for mastering and track order.

J.J. Johnson asked me to produce his albums mainly because he wanted me to choose the takes during the recording and to tell him if another take was necessary or not. For some reason he trusted my judgement. You must know the work well of the artist you are working with. Knowing the artist’s playing live as well as recorded work helps you to judge if what you hear is the best of what they can do, but everything must be done right on the spot without taking too long to make decisions.

Most jazz recordings are done in one to three days. It is not only a question of budget, it is also because great musicians are very spontaneous and get bored quickly if the session takes too long. A lot of masterpieces have been done in just few hours. It is a question of preparing well for the session and also the trust between the producer and the artist.

Regarding my work I would always consider it as coproducing with the artist. Some producers are musicians or arrangers like Teo Maceo or Larry Klein, others are engineers some are professional listeners. I would fall in this last category. Listening to the artist before the session, listening to the music during the session and listening to the mixing engineer, the music and the artist during the postproduction process.

There are a lot of great producers but none of them can do a great album without great artists. Some artists like to work without a producer. It is their choice, and their talent will shine anyway. I still think that they should have somebody they trust that could help them to deliver their best.

4) Taking us up to the present, talk about the evolution of your newest imprint, Artwork Records

Artwork Records is my first experience with an independent label. Before that I only worked for Polygram or Universal labels. The difference is that all my choices are only driven by my own personal taste. I would never sign an artist on this label for commercial or political reasons, or because of corporate strategy and need.

We released 5 albums in 2023 and we will certainly release 5 in 2024. I don’t want to do more that that. It has to be very selective, and I want to have the time to focus on each individual project. As I’ve always done, I’m working with American artists as well as French artists. I believe that the greatest French jazz artists bring their own poetic language to this African American artform. It was obvious for Django Reinhart and Stéphane Grappelli and today’s artists like Alain Jean-Marie, Baptiste Trotignon, Oan Kim, Daniel Humair, Christian Escoudé, Laurent Cugny, Jacky Terrasson or Bireli Lagrène; all who are still contributing to the richness of this music. As a French person I feel very close to this approach of the American idiom with a French accent.

I also have had the good luck to work with some of the greatest American jazz artists and I want to continue to do that for the rest of my life, but I will always believe that this music has no borders.

5) Correct me if I’m wrong but your first two Artwork Productions are solo piano by the great Kenny Barron and the emerging Sullivan Fortner. Why those two pianists, and talk about both in the solo piano format.

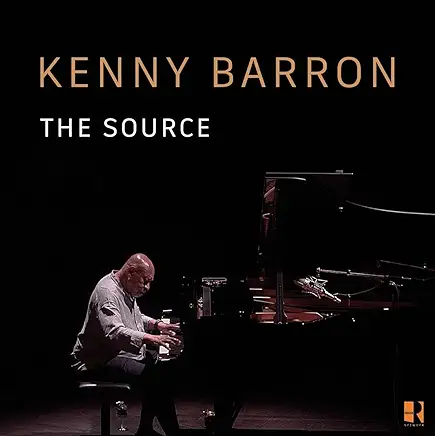

When I decided to create Artwork Records my first call has been for Kenny Barron. The fact that he agreed to record for my new unknown label was very important to me. It gave me confidence to go on. If Kenny is with me, I feel that there is no limit as I don’t think there is a greater jazz musician on earth than Kenny. He represents to me all the historic qualities defined by the creators of this music, a master of his instrument, an improviser with no limit to their imagination, always swinging, a unique and sensitive ballad player, open minded to all the great music cultures, and a great composer. Kenny is also a gentleman and a humble person. In fact, his humility makes him even more impressive. In spite of that, I am working with him on and off for more than 30 years and I am still very intimidated by this gentle genius!

When he told me that he wanted to do a solo album I could not be happier. It was his first solo project in 30 years. I got his favorite Steinway piano in Paris; I rented the beautiful Théâtre de L’ Athénée for the quality of its acoustics, as well as its magnificent architecture. I invited about 15 people to attend the recording session to bring some human warmth and then Kenny delivered this spontaneous masterpiece.

My second call was for Sullivan Fortner. I had signed Sullivan ten years ago on Impulse where he released 2 albums. Since then, he did not have another project under his name. I was thrilled to get a positive reply from Sullivan as I consider him the most important pianist of his generation. I still have the feeling that he is not recognized for the magnitude of his real value. He is much more innovative and creative than his low-key attitude might suggest. He had 2 projects that he wanted to release, one was a piano solo album produced by Fred Hersch and another one more experimental on which he was playing all kinds of keyboards and other instruments. Both projects held equal importance for him. After discussing he convinced me these 2 projects must be released as one under the form of a double CD. He called it Solo/Game.

The piano solo part for me is as innovative and groundbreaking as the “experimental” part. He is already influencing all the younger generation of artists and this project is certainly a milestone in the history of jazz piano.

Regarding the art of piano solo: I think that it is the highest level of excellence and there is a long list of masterpieces in this format. I had the chance to record piano solo albums by Randy Weston (Marrakech In the Cool of the Evening), John Lewis (Private Concert), Hank Jones (A handful of Keys) and I could see, and feel the amount of concentration of these masters involved in this challenging exercise. It is very often beyond styles, bebop, stride, blues, free , swing…

It is just a dialogue of the artist with himself through the instrument. When a journalist asked Kenny Barron about the source of his inspiration for this recording, he just answered: “The piano.” If it is a great piano, he is happy and inspired. This is a very intimate relationship between the artist and, in this case, Steinway & Sons.

Some of my favorite albums are piano solo recordings: Monk “Solo“, Hank Jones “Tiptoe Tapdance“, Randy Weston “African Nite“, Charlie Mingus “Plays Piano“, Fats Waller, James P. Johnson … but I am also a big fan of the great Classical piano players like Alfred Brendel, Samson François, Sviatoslav Richter… and their interpretations of the classical repertoire. All the jazz piano masters studied the European classical composers, and it is certainly mostly in their solo works that you can hear this influence.

6) Tell us what’s up next from Artwork.

We’re going to release on March 8th the 2nd album of saxophonist Oan Kim’s, called “Rebirth of Innocence” and on May 10th a new Kenny Barron quintet project with Immanuel Wilkins, Steve Nelson, Kiyoshi Kitagawa and Johnathan Blake.

In the Fall, we will have a Sullivan Fortner trio album, a septet project of pianist Micah Thomas and the French 4 pianist’s group PIANOFORTE with their debut album. This quartet of great keyboardists is comprised of Baptiste Trotignon, Éric Légnini, Bojan Z and Pierre De Bethman. You may not know some of these pianists here in the US, but you probably know Baptiste Trotignon from his co-lead project with Yosvany Terry.

I am also working on unreleased historical recordings…more news on that to come!