I was one who admittedly questioned the late 90s/early 21st century seeming media blizzard on behalf of The Bad Plus, the innovative trio for which Ethan Iverson served so splendidly as its original pianist. Subsequent personal sightings of TBP proved that yes, these guys were onto something interesting, all media acclaim aside. Since then I’ve found Iverson to be an eminently reasonable man unencumbered by what might accompany the level of runaway ego or undue hubris that sometimes seems to attach itself to musicians less evolved amidst that initial level of TBP hype. Notably his efforts have included some very productive writing on jazz and related subjects, for JazzTimes magazine and for his own Transitional Technology blog, which you can find at https://iverson.substack.com.

For the late 2018/early 2019 holiday season Suzan and I spent a lovely time at Umbria Jazz’s great winter event in scenic Orvieto, traditionally held the week after Christmas climaxing New Year’s Day. And what a rewarding experience it was, including an opportunity to observe Ethan Iverson at work on a fairly large scale project.

Umbria Jazz had commissioned Iverson to sort of reimagine the genius pathbreaking pianist Bud Powell and his music. For the occasion Ethan was joined onstage by guest trumpeter Ingrid Jensen, tenor saxophonist Dayna Stephens, the superb house rhythm section of bassist Ben Street and the eminently crafty master drummer Lewis Nash. The core band for Ethan’s Bud Powell re-imaginings was the Umbria Jazz Orchestra. For this project Iverson contributed eight original compositions in the spirit of Bud, and arranged seven Powell originals – including his classics “Tempus Fugit,” “Celia,” “Un Poco Loco,” and “Bouncing with Bud,” the inevitable Monk encounter “52nd Street Theme.”

The results of that commissioned work are borne out in one of this writer’s picks in Francis Davis’ annual critic’s poll for 2021’s finest releases, Bud Powell In The 21st Century released on the Sunnyside label. Having an opportunity to hear this project evolve over the course of a week is one of the beauties of a great festival like Umbria Jazz Winter, in the inviting confines of Teatro Mancinelli.

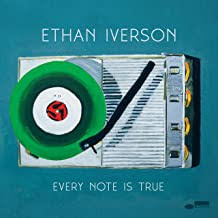

A few weeks ago Ethan Iverson struck again, this revelation was his debut recording for the classic Blue Note label, Every Note is True, this time in trio mode with the auspicious rhythm section of bassist Larry Grenadier and NEA Jazz Master drummer Jack DeJohnette. Clearly some questions were in order for the intrepid Ethan Iverson.

I know you’re somewhat of a historian of this music, so given the hallowed place Blue Note Records holds in the history of recorded jazz, what’s your sense of making your Blue Note debut?

Blue Note is at the top, of course. It’s very odd for me to consider all this – because I can’t believe how lucky I am – but The Bad Plus debuted on Columbia when that label was still a real force for jazz, thanks to Yves Beauvais’s sting at A&R. I love Manfred Eicher and ECM, and the projects I’ve done there were wonderful experiences, perhaps especially the duo session with Mark Turner, where Manfred gave some remarkable feedback in the studio. Most recently I gave my Bud Powell in the 21st Century tape to Francois Zalacain, who holds it down at Sunnyside. God bless Sunnyside too.

The Blue Note catalog is unrivaled. The whole human race loves the classic Blue Note records! But I also really admire Don Was’ conviction that the music doesn’t stop growing. He’s managed to curate a label that does not rest on its laurels, but stays relevant.

You gotta believe in the music more than the career. If you sit around worrying about the career all day, you won’t make the music you need to make. However, leaving The Bad Plus was objectively a career risk. Putting out a record on Blue Note is proof that leaving TBP was the right decision.

The title of this recording – Every Note is True – is one that some might assume carries a message. If so, what would that message be?

It’s a line from the opening song, but also yes, a message, or even a manifesto. One must believe in one’s own musical opinion, there’s simply no other way to do it.

What went into your selecting such a stellar rhythm section of Jack DeJohnette on drums and Larry Grenadier on bass to make this record?

The 2020 pandemic closed many doors, but it opened up a few as well. I had always wanted to play with Jack DeJohnette. Since nobody had any gigs, Jack was free to meet me and Larry Grenadier in the studio for two days.

I had worked with Larry a bit, he’s on my record with Lee Konitz. For many he is the ranking bassist of his generation. The first time I saw Larry play he was extremely young and sounding just great with Joe Henderson at Fat Tuesdays, maybe 1993 or so. Larry is a serious virtuoso, but he believes in the traditional function of the bass.

I first saw Jack DeJohnette live at Orchestra Hall in Minneapolis with Keith Jarrett. I believe I was only twelve years old. The experience was so profound I bought a set of drums the very next day. He’s one of the greatest drummers of all time, full stop.

Obviously you have a whole universe of tunes to select from, not to mention your own original compositions. So how did you choose these particular ten tunes for this record?

After leaving The Bad Plus I had a lot more space around my head, and surprised myself by writing a lot more music. Hardly a week has gone by where I don’t think of a melody and write it down. The tunes on Every Note is True are some of the better ones. I selected relatively easy themes that we could learn quickly and record passionately.

Then there’s the opening track, “The More it Changes,” a novelty number with friends, most of whom I didn’t see in person all year but who sent me text messages with their vocal overdub. In the end, one must try to adapt to any circumstance.

As a piano player, who have been your guiding lights?

I know all the jazz pianists, but I love other stuff too. When I interface with literature, movies, or television, it helps me see that parameters of genre are freeing, not constricting. I like genres. Some people don’t believe in them and want to live their life “genre-free.” I have little interest in that perspective. I’m more like, “What is the genre?” If we know what genre it is, then we can fill the container with the right kind of material.

Everything “new” is a combination of previous things. What matters is how well you know each element you’re combining. If you’re writing a supernatural detective story, you need to ask yourself how well you know the supernatural genre and how well you know the detective genre. People often know one side more than the other. That’s always been an issue in the arts, but here in the postmodern age of the 21st Century, everything’s a click away. It’s all one big mashup. The question is how well you can control all the aspects you’re dialing in to the final product.

Sometimes a college music student will say, “I don’t want to be labeled. Don’t even call it jazz; it’s all beyond category.” I get it, but at the same time, any single phrase you can play on an instrument has a heritage, so what lineage are you in? And if you know your lineage, you can accept it or work against it.

To get back to your question, three of my many obvious jazz piano influences are Thelonious Monk, Paul Bley, and Mal Waldron.

However, part of what makes me distinctive as a player are frankly European Classical elements. Indeed, I believe no other “jazz” pianist has done exactly what I accomplished in The Bad Plus’ The Rite of Spring, which was merely reading down a score filled with thousands of notes alongside a fierce rhythm section.

In pure musical terms, I play a lot of triads. Most of my peers rarely play pure triads. At the session Jack DeJohnette said to me, “You play a lot of triads. That’s really different.” I responded “Jack, one of the first places where I was so impressed with a pure triad was the ending of your piece “Blue” (Jack recorded that on piano on a Gateway album.). Jack then taught me “Blue” in the studio and it ended up on Every Note is True!

As a musician whose own interviews of fellow artists and whose writing exploits appear to be expanding, how do you balance your roles as musician and as writer?

I feel close to certain heroes who also did historical work. Johannes Brahms collected old scores and oversaw editions of then hard-to-find scores of Francois Couperin and others. Mary Lou Williams assessed the whole canon eloquently, and her “Tree of Jazz” is one of the finest pedagogical tools ever produced. Donald Westlake wrote some truly significant pieces of literary criticism in addition to publishing almost 100 crime novels.

The journals of pre-internet artists often make for great reading. In the internet age, the minute you think of something, you can put it online, for better or for worse. But my public advocacy for music writ large is also my journal. It certainly interacts with my performances and recordings in a very literal way.

So what’s next on Ethan Iverson’s agenda?

Every Note is true was released February 11th, and there were two record release concerts, Feb. 7 in Boston and Feb. 11 in Brooklyn. Jack recommended Nasheet Waits as a sub for the live gigs, which was perfect.

In addition to the trio repertory with Larry and Nasheet, the two concerts featured the 45-minute suite “Ritornello, Sinfonias, and Cadenzas” for eight horns and rhythm section. This was the American premier of a 45-minute suite commissioned last year for the Umbria Jazz Festival. It’s really pretty damn good IMO, I turned 49 on Feb. 11, and – while this is not visible on the surface yet – the rough plan is to spend the next stage of my career in my 50s and in the far future less as a trio pianist and more as a formal composer. Eventually, in retrospect, those concerts may mark the transition.

This coming year I will be playing with the Billy Hart Quartet quite a bit, in a longstanding group with Mark Turner and Ben Street. There’s also work as a composer or arranger with the Mark Morris Dance Group or Dance Heginbotham. Truly I am lucky to have so many wonderful collaborators. From the outside, it might look hopelessly eclectic, but for me it all follows the same thread. Every note is true!