As writers the craft of journalism & criticism demands objectivity, no matter what the genre. But we’re human, we all have certain favored areas of our particular pursuit. Writer Bill Shoemaker, publisher of the penetrating online journal Point of Departure (http://www.pointofdeparture.org) certainly respects the tradition and has a broad-based sense of the music, but in particular he has long expressed a never-ending curiosity for the edgy, the experimental, and the free.

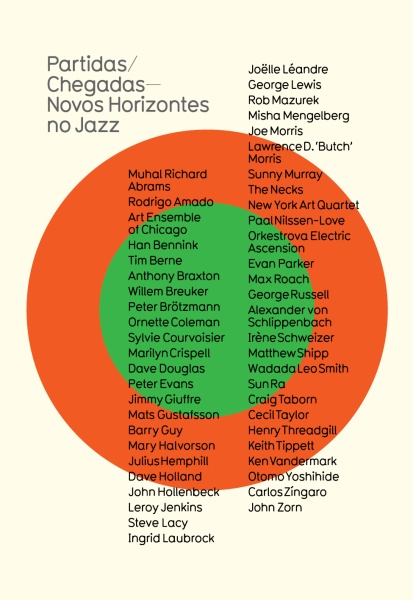

Last Labor Day Weekend as we sat in the unusually balmy clime of Chicago’s lakefront in Millenium Park awaiting another splendid night of the Chicago Jazz Festival, Bill laid a fresh copy of an intriguing new book on me of short critical essays, titled Arrivals/Departures – New Horizons in Jazz (pub. Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation), for which he served as one of three contributors. From the jump the list of names on the book’s cover revealed it as a chronicle of sorts of some of the true restless seekers in contemporary music. Clearly some questions were in order for Bill Shoemaker.

It often happens that books like Arrivals/Departures – New Horizons in Jazz are published to fill at least a perceived void in the literature. Where do you see this book fitting as far as fulfilling a need for information on these artists? Would it be safe to say that this book is somewhat of an encyclopedia of some of the freer forms of modern jazz? Where/how is this book available to the public?

The book came about through unusual circumstances. Stuart Broomer and I were approached at the 2012 edition of Jazz em Agosto in Lisbon by the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, who produces the festival, to write a book coinciding with the 30th edition of the festival in ’13. At first, we thought they wanted an essay from each of us for a booklet, so were quite stunned when they proposed 100 essays on artists who had performed at the festival. This should have tipped us off that they were not really in touch with what it takes to write such a book.

We got them down to 50 – 25 at approximately 1,250 words; 25 at 750 – and then Stuart and I drew up a list of artists and divided them between us; it was like kids with baseball cards in a way. We then submitted a list, but we were overruled on some names. Randy Weston, for example, was nixed in favor of someone I refused to write about – another hint that trouble was ahead.

When we left the festival in mid-August, we basically had an agreement. Its finalization was held up for almost two months, which was potentially lethal given the short time we had to write. The administrator – Jose Pinto – took a lengthy holiday (he deserves them, he said in an email) and then, for weeks, he inexplicably could not confirm that Stuart and I were not subject to Portuguese income tax. Given that we had to deliver all the copy by the end of February, and that an unusual amount of other work came my way in the interim, I decided to sub out half of my work to Brian Morton. By this time, my relationship with Pinto was deteriorating – I think it was my suggestion that he just walk down the hall to the comptroller’s office on the tax issue.

We then had other issues: They dragged their feet on whether American or British English would be used (I’m used to Americanizing Brian’s writing, but at the 11th hour?); they insisted that Otomo Yoshihide be alphabetized as a Y name, even though Otomo is his family; we had to do all the line editing and page proofing; it went on and on. It was a stressful four or five months. The joke is that by spring I had a light case of The Shining. Then there is the cover, which looks like a middle school absence list on which a teacher placed his/her coffee cup. They managed to cram 50 names on the cover, but intentionally omitted ours – some nonsense about the current European protocol of academic volumes with multiple authors, they said – all of which brings me to their lack of marketing chops. True: jazz consumers are interested in the subjects of a book, but they are also interested in who wrote it. Many jazz fans use critics as barometers for better or worse, be it us, Stanley Crouch or Howard Mandel. Nobody seems to know the book’s list price. The ace kicker was that the Portuguese edition of the book was not ready at the start of the festival. BTW: The title is theirs, not ours.

I bring all this up not only to make it clear that writing a book is neat in theory, but something else altogether in practice, but to explain the somewhat inchoate state of the book. It’s not really an encyclopedia or a critical history. The book is 50 short essays about musicians who played at this particular festival over 30 years. It was an assignment; left to our devices and an appropriate production schedule, we would have come up with a more interesting template. Don’t get me wrong: for what it is, it is very solid. I’ve been contacted by a couple of the musicians included in the book, and their response has been very enthusiastic – that’s really my measure that we got it right.

I do think there remains a void in the literature about the avant-garde. It shrinks with each book that appears on the subject, including this one. I think we shed light on some newer artists – and some familiar, even iconic artists, as well. But, I do think the idea of a definitive text on the jazz avant-garde is increasingly elusive – the music is just evolving too rapidly. The idea that a definitive assessment can be made about an artist in their 30s or even 40s – say, Mary Halvorson – is wrong-headed. It is equivalent to saying Four Lives in the Bebop Business (a book I cherish) is the last word on Cecil Taylor. So, I think it’s a matter of having more books written by a more diverse population of writers – if that happens, then at least we have a detailed composite picture.

As to where or how to get the book: I have no idea.

Many of the artists featured in the book are identified with the so-called jazz avant garde. That’s always been a loaded term, but you know how it is with our collective need to categorize music and musicians. What’s your sense of that term avant garde and does it really fit these musicians featured in this book?

Almost any term in the discussion of jazz – including “jazz” itself – has been loaded at one time or another. In a way, it’s good that “avant-garde” still has some polarizing sting to it. I respond to the term “avant-garde” in two ways: as shorthand for envelope-pushing, non-commercial, too-original-for-words music; and as a historical marker when discussing the late ‘50s and ‘60s. I would say the term is fitting for the artists in the book, but not necessarily for the entirety of their output. I think Jimmy Giuffre is a good example of this. Perhaps it is partially our fault that, generally, we have not sufficiently educated our readers, but it remains a fact that most people have a much easier time with avant-garde visual art than with music – they can process Jackson Pollack better than they can Ornette Coleman. Mind you, we’re talking about art that’s 50 years old, so it shouldn’t be a stretch for an educated, upscale demo – but it is.

Arrivals/Departires – New Horizons in Jazz features a balance of U.S. and European improvisers. In terms of their training, experience, where they come from and their overall music perspective, what differences do you detect in the creative outlook of artists from the U.S. and those from Europe in terms of how they convey their music?

I was in the crossfire of the US v. Europe jazz controversy for years – Americans thought I was Eurocentric, while Europeans thought I was an American chauvinist. I think that speaks to the liability of being inclusive in your views. I always fall back on something my dad said about Europeans he met during WWII: They’re just like us, except they’re different. Certainly, the European social/cultural/political context is distinct from ours, but that doesn’t mean you can’t love something from a different context. There are few Americans who have taken Coltrane to heart as have Brits like Paul Dunmall, Evan Parker and the criminally neglected Art Themen. You would be hard-pressed to find someone with brighter insights into John Carter than Ab Baars. I really can’t think of an American currently who has that Big Sid Catlett swing [down] like Han Bennink – but that’s just part of what he does. Certainly, their individual aesthetic filters yield music that does not always bear much resemblance to American jazz; but if they did, there would be those who would say that they’re pale imitations. Conversely, there are American drummers who try to play like Paul Lovens, guitarists who try to approximate Derek Bailey; the list is long. So, I think the eggs are thoroughly scrambled.

Talk about your online journal Point of Departure and the perspective it chooses to deliver.

To paraphrase the old ESP slogan: It’s the writers who determine what you read in Point of Departure. I think saying PoD has an avant-garde-centric orientation is basically accurate, although the current issue has long pieces on Woody Shaw, Pee Wee Russell, Major Surgery (a British electric band from the ‘70s) and The Smithsonian Collection of Classic Jazz. BTW: Anyone who bemoans the death of long-form jazz journalism obviously hasn’t read PoD. We regularly run pieces of 3,000 words or more. I wish I had the time to continue the roundtables – they were always lively – but, otherwise, I’m OK with where we’re at in terms of content. I’m encouraged by the contributions of newer voices like Clifford Allen, Jason Bivins, Troy Collins (who is also an invaluable part of the production team), and Michael Rosenstein. Veterans like Brian, Stuart, Art Lange, Ed Hazell and Kevin Whitehead continue to motivate and educate me. Going from six issues a year to four was a necessary change – I’m amazed I haven’t completely burned out – and it now seems like a sustainable pace: writers have more time to write, readers have more time to read, and I actually have time to write fiction, shoot pool and hang out. The one thing I haven’t accomplished with PoD is completely squelching the idea that it is a blog, a term like “avant-garde” that is going to be there, regardless.

What’s forthcoming in P.O.D.?

The thing about PoD is that I only really don’t know what will be in the next issue until a couple weeks out from publication. Art rarely knows what he’ll be writing about until then; same with Brian, sometimes. I am continually amazed by their ability to produce incisive essays in a matter of a day or two. And, Art delivers absolutely immaculate copy to boot – I had to tease Art that Troy found two extra spaces when he formatted Art’s Pee Wee Russell piece. Obviously, record reviews have to be sorted out earlier in the cycle, but even then there are last minute additions – and crises that prevent delivery of a review or two. I think I’m writing about Jimmy Carter’s jazz picnic for the December issue, but that could change at any moment – really.

Just to give you a taste of what’s in store when you visit Bill Shoemaker’s online journal Point of Departure (http://www.pointofdeparture.org) here are the contents of the most recent issue:

Issue 44 – September 2013

Page One: a column by Bill Shoemaker

Gerald Cleaver: Surrendering to the Experience: an interview with Troy Collins

A Fickle Sonance: a column by Art Lange

Where’s Borderick?: by Kevin Whitehead

The Book Cooks:

Improvisation, Creativity and Consciousness:

jazz as template for music, education and society

by Edward W. Sarath

(State University of New York Press; Albany)

Far Cry: a column by Brian Morton

The Art of David Tudor: by Michael Rosenstein

Moment’s Notice: Reviews of Recent Recordings

Ezz-thetics: a column by Stuart Broomer

Travellin’ Light: Dominic Lash

Archive

Contacts

Publisher: Bill Shoemaker

Production: Robert Winkle, Troy Collins

Pingback: Ornette Coleman and harmolodics | Bibliolore