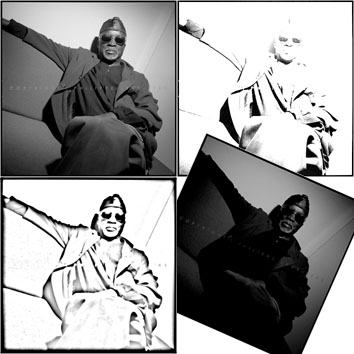

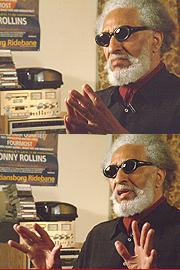

DOUGLAS EWART: in a rare moment of relaxation

for a man who seems never to sleep

The group photo of modern day renaissance men should include Douglas Ewart. A saxophonist & all-round woodwind specialist and composer from Jamaica who emigrated to Chicago as a young man and currently splits his time between the Windy City and Minneapolis, is an intrepid instrument maker, award-winning visual artist, teacher, soothsayer, and all-around seeker in the truest sense of the word. The former president of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), Ewart is one member of that famed musicians’ collective who chose to stay in the midwest and ply his craft, though he is a world traveler whose musical exploits may actually be more familiar to overseas audiences than even in his own backyard. A man of many and varied — often unusual and unprecedented — projects, commissions, and boundless ideas, when I heard about one of his latest projects I had to ask questions.

Douglas is a man who delights in making something special out of found objects. Simply walking city streets he’ll spot something useful for his projects that many of us wouldn’t give a second thought to. Visit the home of he and wife Janis Lane-Ewart, one time AACM administrator and current general manager of Twin Cities community radio station KFAI "Fresh Air Radio", and one could conceivably spend days digging through the artifacts and unusual objects of their many travels. This latest effort was to be a project not only involving his original music… but spinning tops! Read on…

You’ve always struck me as a kind of improvising renaissance man — musician, composer, visual artist, educator… How do you juggle all those balls and maintain balance in your career?

I thrive on being engaged in a multitude of things. I have been working at developing several skills over many decades; therefore, I have attained some level of profiency at several occupations. I feel something is missing if I’m not working on several projects simultaneously. If you do a little on a consistent basis, you would be surprised how much you can accomplish. I always have some projects that I am working on that are in stages of development, some of these projects take years to complete. I don’t mind that some things take a long time to complete. If you are working on various projects you have something to look forward to doing each day, and that is key to being enthusiastic about life, being able to work and achieve results is a wonderful feeling. I feel that we complain too much about life, about what is not right. Be grateful to be able to walk and talk on your volition.

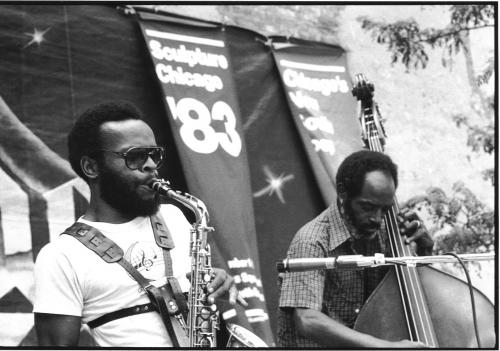

DOUGLAS EWART (saxophone)in performance with bassist Donald Rafael Garrett

at an event combining two of his passions: music & sculpture

You have to make time for the things that you feel are important to you, as it helps in defining your well-being. If you say ‘I don’t have time to do this or that’ then you may never get those things started or completed. However, if you get started and do a little at a time, one day you can stop everything else and complete that project or item. I have a motto: "five-fifteen minutes a day will get you there." If you say I love to play music, paint or roller skate but I don’t have time, then you get out of practice, and you get out of the mind set to do the particular thing. You get out of courtship with that thing and that thing rejects you when you go to it, as you have not been there for it; things have a life of their own and they demand attention. But if you take your easel out and set it up, make one stroke a day with your paintbrush you will soon have a completed work. If you practice your instrument regularly even if you don’t have a lot of time, you develop your embouchure and when you do have time you will be in the proper mental and physical state to extend your time allocation to that thing, study or discipline. Consistency creates momentum and continuum. The discipline is the crucial element. It reminds me of saving money. If you cannot save when you have small amounts of money you won’t or can’t when you have a lot because you have not developed the discipline of saving.

I understand your latest project — which like so many of your efforts seems to combine your music and your visual arts & craftsmen skills — involves composition and spinning tops.

Yes, I have been contemplating a work entitled "Ewart Sonic Tops" for several years now. The idea is to make at least two hundred or more tops that make sounds. So about two years ago I decided I better get started with the construction of the tops if I was to accomplish the colossal task. I have completed over two hundred functioning tops from bamboo, cups, saucers, vases, candle holders, LPs. CDs, DVDs, clarinet bells, toilet plungers, plastic jars, bowls, globes, wheels, etc. The tops are utilized as sound and movement generators in my work. The tops make flute like sounds, rumbling sounds, rubbing sounds, rattliing sounds, humming sounds, accelerating and decelerating sounds, Doppler effect and some indescribable sounds.

The movements of the tops are quite varied based on the materials they’re made of; equilibrium, texture of the surfaces on which it is spun, the velocity of the launch, etc. The tops have personalities just like people; some tops are steady and remain in one place from the initial launch, some tops are erratic, some flit about, some spin for a long time, some spin for a short time, some are persistent and continue to spin even when they encounter obstacles, and some are very reluctant to stop spinning and bob & weave in an effort at resisting gravity. The tops are launched or spun by twirling or twisting them with the thumb and index fingers, by holding the palms of the hands in vertical and parallel manner facing each other, and placing the spindle attached to the top between the palms, then in a rubbing or rolling manner [you] twist and release the top.

"Ewart Sonic Tops" is a multi-dimensional work and concept. Sound, music, movement, visuals, tactility, structure, practice and improvisation are endemic to all my current endeavors as an artist. I want to link children and adults in a very basic yet complex manner. I want to magnify the links and overlaps of play and work, laughter and seriousness, esoteric and generic, ethereal and earthy, mythology and pragmatism, gravity and levitation, meditation and concentration… the fine lines between child and adult, imagination and realism.

Musicians from Jamaica are almost automatically stereotyped as being either reggae musicians or somehow part of that milieu. You completed a very interesting project earlier this year between George Lewis (brilliant trombonist-composer, Director of the Jazz Studies program at Columbia University, and author of the definitive volume on the AACM A Power Stronger Than Itself), the recently-passed Jamaican jazz trumpeter and festival impressario Sonny Bradshaw, and yourself. What was the genesis of that collaboration and how did it turn out?

"In Search of The Lost Riddim" was a magnificent project! Herbie Miller proposed the project to George Lewis, and with consultation from several people, including me, the project was distilled. Herbie Miller is a historian, musical impressario, and avid supporter of the arts. The project was sponsored by The Center for Jazz Studies at Columbia University and Harlem Stage and took place at Aaron Davis Hall last February. The program featured musician-composers Cedric Brooks (tenor saxophone), Ernest Ranglin (guitar), Orville Hammond (piano & flute), Wayne Batchelor (bass). Desmond Jones (drums), Larry McDonald (conga) and myself on reeds & percussion. Sonny Bradshaw was unable to participate due to illness. [Editor’s note: The veteran musician and Jamaican jazz festival producer Sonny Bradshaw, who once expressed skepticism about the original compositions of Ewart and Lewis after witnessing one of their performances, passed on to ancestry last October 10.]

We played some Jamaican traditional folk songs, Rasta liturgical pieces, and some ska. Some of the songs were "Never Get Weary", "Holy Mount Zion", "Liza", "Bridge View" by Roland Alphonso and several original works by Cedric Brooks, Ernest Ranglin, Orville Hammond, and me. We had a round table discussion convened by Herbie Miller that included Ernest, Cedric, Larry and myself. We discussed the music, art, Rasta, and other pivotal aspects of Jamaican culture. The roundtable was followed by the concert. It was a delightful project and was part of a dream fulfilled as I got to perform with one of my idols, the incomparable Ernest Ranglin. I knew Ernest as a boy but never got to formally meet him and to have the pleasure and privilege to play with this master musician was a highlight of my career. I love reggae and ska and have played in various bands that play those branches of music. I feel all types of music are critical and lend themselves to be creatively rendered. It’s the quality and creativity that counts.

One of the more fascinating elements among so many in my reading of George Lewis’ excellent history of the AACM, A Power Stronger Than Itself, was learning more about your history and evolution from Jamaica to Chicago to joining and eventually becoming president of the AACM. I was particularly interested to learn that you had much contact with the legendary Count Ossie as a young musicians. Talk about those experiences.

I knew Count Ossie when I was a boy growing up in eastern Kingston, Jamaica. Count didn’t live far rom my family’s home. I used to go to his house on Saturdays to hear reasoning and to listen to the drums; these gatherings were called groundations. My grandmother was a Seventh Day Adventist and I attended church on Saturdays. I would go to church to establish my attendance and then go to Count’s without my grandmother’s knowledge. I saw all the great Jamaican musicians there: Donald Drummond, John Dizzy Moore, Rico Rodriguez, Roland Alphonso, Tommy McCook, etc. It was a great experience for me as I was exposed to a multitude of philosophies, personalities, intellectuals, artists and everyday heroes and survivors. Count knew several members of my family and he was always welcoming.

When I heard Count [Ossie] it was a powerful, and encompassing feeling. The drums made you feel powerful, elated, connected, and confident. I was inspired and wanted to play the repeater, which is the drum on which Count was a master. Count Oswald Williams came from St. Thomas and was schooled in Kumina drumming, which was one of the musical blue prints for Akete or Nyahbingi Drumming. Kumina is an Afrocentric polytheistic religious movement and music; drum music is a central component.

I did fashion some drums from various cans and attempted to play them when I was home. I eventually had an opportunity to try some of the drums at Count’s camp. When I was an adolescent I moved into the Wareika Hills for a period and lived on Douglas Mack’s and Alvin "Powdy" Bryant’s camps. It was a powerful experience about what self-determination means and costs. It was not fashionable to be a Rasta in those days. As Rastas we were subjected to police raids, beatings, illegal search and seizures, arrest, and all too often imprisonment. Fortunately I was never beaten or arrested.

I was also quite familiar with the music of Dizzy Gillespie, Clifford Brown, Charles Mingus, Charlie Parker, Ella Fitzgerald, Franz List, Bach, Dakota Staton, Ray Charles, Louis Jordan, Little Richard, Shirley and Lee, etc. I had a great desire to play the trumpet but did not have access at that time. I migrated to Chicago in June, 1963. I was looking for some challenging, creative music and found the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM). I began attending AACM concers at Lincoln Center in Chicago. The concerts were given every Sunday and I attended faithfully. I eventually met all of the founding and charter members of the AACM. Several people and I began asking the musicians about lessons and the AACM formally launched its school of music in the fall of 1967.

I had bought a trumpet in 1966 but was unable to get what I considered a good sound. I bought a Buescher alto saxophone from Joseph Jarman and began teaching myself to play it. Then I took some lessons from Jarman and joined the AACM School of Music in the fall of 1967. I began studying composition, theory, saxophone and clarinet and taught myself how to play the flute. We began writing compositions right away at the AACM’s School of Music and presented them in our recitals. I also formed several bands: the Cosmic Musicians, and The Elements. I also began playing with some rock and roll and Rhythm & Blues bands. Joseph Jarman was one of my chief mentors and I began playing with him during those years.

How did you eventually rise to become president of the AACM?

After attending the AACM School of Music, I became a member in 1968; it was a very informal induction for me. The usual process is formal and one has to be voted into the organization. My dedication and commitment made for a very natural kind of induction into the AACM. I used to assist with publicity, concessions, and monitoring the door at concerts. I became president during the migration of the founding charter members [from Chicago] to New York and Europe. I was installed in 1979 and was president for seven consecutive years. It was a very great period for the AACM as we were assisted with some grants from the National Endowment for the Arts and other philanthropic institutions. We were able to hire Janis Lane as an administrator. She was very able and we were very successful. We rented a space that centralized our activities. The AACM Space housed our offices, school, and concerts. I resigned my post as president because I was awarded a US Japan Exchange Fellowship in 1986. I have since served as chairman and co-chairman as recently as the early part of 2009.

What would you say about the AACM as it approaches its 50th anniversary as the most significant collective of improvising artists of the latter half of the 20th century?

The AACM has been a tremendous organization in the field of music and beyond. We have survived and thrived. The AACM has some of the most brilliant theorists, conceptualists, composers and music practitioners the world has ever known. When you think about it, the AACM has a staggering number of monumental accomplishments. Some of its pivotal achievements in addition to the music are longevity, consistency, and perseverance. We have stayed together because many of us realize the importance of the collective. We have stayed together because of mutual respect and the recognition that collectivity is what made it possible for us to survive as a people.

Since you are an artist who is constantly developing new approaches and new projects, what have you got on the burner these days?

I am now working on a drum piece. I’m constructing a set of drums using discarded rackets, trampolines, crutches, etc. I hope to get it mounted sometime in 2010 or 2011. I mentioned the Ewart Sonic Tops earlier. I am very interested in utilizing some of the experiences and games of childhood to bolster our current conducts. The tops piece was very successful as it brought people from all backgrounds, walks of life, and age groups in a very engaging, playful, reflective, skillful, problem solving activity. The work emphasized the communal and individualist aspects of play and work. I want to continue using sound, visual arts, movement and poetry to galvanize our human family. I feel that pieces like Ewart Sonic Tops can bring people together in a manner that enables them to have substantive and rewarding exchanges in a very playful and relaxed environment.

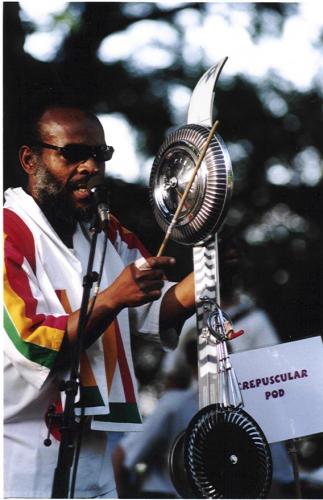

EWART exploring one of his inventions

You seem to have recorded your work rather sparingly — or perhaps it’s that you’ve been afforded the opportunity to do so sparingly. Where does documenting and releasing your music for public consumption rank in importance for you?

Documentation and its dissemination are crucial for me. Howevere, I am not willing to give my work away just to have it out in the public. I have had offers from companies but not the kind of offers that I am willing to take. I have been putting out my work on my Aarawak Recording Company label. The process is slow but sure and I have total control over all aspects of the product. Playing is far more iimportant to me than making records. I constantly record my performances and will continue to put them out when it is feasible. There is no lack of product. I say to all artists: document, document, document! If you have product documented you are prepared to package and disseminate when that opportunity becomes available to you. I have a new CD Velvet Fire which will drop on December 13; its dedicated to [saxophonist and early AACM membere] Fred Anderson.

Talk about your work as an educator.

I’ve been involved in education a great part of my life. I was a tutor at the AACM School of Music while I was a student and I had a work-study job in the music department at Loop Junior College. In fact, while I was a student at Loop I co-taught a course in Black Music with Ahmed Ben Bayla. I really got my teaching acumen together when I worked for Urban Gateways doing residencies in public and some private schools as an artist-in-residence. Those experiences really equipped me to go anywhere and teach. It was the most challenging teaching job due to the lack of discipline that so many of our young people are exposed to from their inceptive years. Parents lack discipline in what to eat, when to eat, how to scold, how to talk to their children, how to think, etc. I worked for Urban Gateways for over ten years. I also ran many workshops in instrument construction and performance in various communities as an independent artist.

Twenty years ago I moved to Minneapolis and began teaching in the public and private schools for Compas, who used the Urban Gateways model for their organization. I used to be a guest lecturer at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago. After moving to Minneapolis I was offered a visiting artist job, which evolved to a professorship. I’ve taught instrument making, music history of Latin America and the Caribbean, music of Asia and the Pacific, Contemporary Music Seminar and Jazz History. I love teaching as it compels me to do vigorous and rigorous study. I love to read but being a teacherr fuels the quest for knowledge ten times over. My music history classes cover a lot of ground. If you are really going to understand the music you have to know something about the religions, politics, foods, classes, skills, and cultural underpinnings of the people.

Any closing thoughts you’d like to share?

I want to continue to make art that brings the youth and the elders together. I want to see the US government invest a billion dollars in the arts. We have spent trillions on implements of war to no avail. When we spend on the arts the money changes hands incessantly and we have positive products as a result. Real detente begins with the arts. I believe in the trickle up theory! The government should have stimulated our economy by giving the poor people some real money… like $3-500,000 per family. Instead the money was given to the same crooks that put the world economy in shambles and they are still stealing and blocking poor people from accessing desperately needed funds. But the public is too silent and silence means consent. We must take to the streets and make our power known and felt in massive non-violent protest.

Please get yourself a permanent cup to [purchase] your coffee and tea from carryout places. If more of us do this we will reduce our waste markedly. Let’s continue to support President Barak Obama. His tasks are formidable and numerous, and we have a lot of people and systems that are averse to change. Truth and change are costly, challenging and very difficult to implement. This is a great country but we have miles to go in human relations.

Select Douglas Ewart Discography

As leader

Douglas Ewart, Red Hills, Aarawack

Douglas Ewart, Bamboo Forest, Aarawack

Douglas Ewart/George Lewis, Jila-Save!, The Imaginary Suite

Douglas Ewart, Angels of Entrance, Aarawack

Douglas Ewart, Bamboo Meditations at Banff, Aarawak

Doglas Ewart, Songs of Sun Live, Innova

Douglas Ewart Quintet Visionfest Vision Live Quintet, Crepescule IV in Powderhorn Park, Thirsty Ear

As sideman

George Lewis, Chicago Slow Dance, Lovely Music

George Lewis, Homage to Charles Parker, Black Saint

George Lewis, Shadowgraph, Black Saint

George Lewis, Changing With the Times, New World

Chico Freeman, Morning Prayer, Whynot

Dennis Gonzalez, Namesake, Silkheart

Leo Smith, Budding of a Rose, Moers

Roscoe Mitchell Creative Orchestra, Sketchees from Bamboo, Moers

Diem Jones, Black Fish Jazz, Black Fish

Bams, De Ce Monde, Junkadelic

Muhal Richard Abrams, Lifea Blinec, Arista Novus

Anthony Braxton, For Trio, Arista Novus

Roscoe Mitchell, Maze, Nessa

Henry Threadgill, X75, Arista Novus

AACM, Great Black Music Live, AACM

AACM, A Power Stronger Than Itself, AACM

Roy C. McBride, Live at Third Ear, New Dream Ark

The Visitors, Citizens of the Planet, Mikai Music