This year marks the 50th anniversary of Randy Weston’s signature recording session Uhuru Afrika, certainly a good time to reflect on that singular record in this Randy’s 84th year on the planet. And I’m happy to report that our as-told-to book African Rhythms: The Autobiography of Randy Weston, composed by Randy Weston, arranged by Willard Jenkins, will be released by Duke University Press this fall, just nine years in the making! The lead-up to, the story of, and behind the making of Uhuru Afrika will be told in great detail in the book, but in light of this 50th anniversary of it’s recording I thought it was a good time to reprise the piece I contributed on the subject to DownBeat magazine’s February 2005 issue.

Freeing His Roots, The Making of Randy Weston’s Landmark Opus Uhuru Afrika

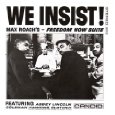

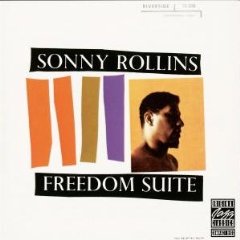

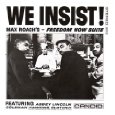

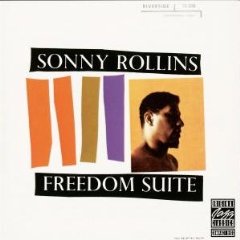

A social awareness swept through the jazz community around 1960. African-American jazz artists began to assert their heritage, embarking on a cultural quest in an atmosphere of racial and social unrest. Between 1958-1961, albums addressing the African-American social lanscape included Art Blakey’s Africaine, John Coltrane’s Africa Brass, Oliver Nelson’s Afro-American Sketches, Dizzy Gillespie’s Africana, Max Roach’s Freedom Now, and Sonny Rollins’ Freedom Suite.

In addition to these albums, Randy Weston asserted his African Heritage with the 1960 recording of Uhuru Afrika, an inspired, historic statement from the pianist/composer. Looking back at the recording of this album, which took place [50] years ago. Weston is a bit defensive when describing his motivations.

"Some people questioned my Africanness. They were afraid to deal with Africa," Weston said. "Some people said we were Black Nationalist because we created a music based upon African civilization. We have so little education about Africa, Uhuru Afrika, was a complete turnabout. We said, ‘Africa is the cradle of civilization. Although we’re in Africa, the Caribbean, Brooklyn, or California, we have this commonality, spirituality and the great contributions of African society within all of us.’"

Weston was raised in a home of keen cultural awareness. The sancitity of his African heritage was a constant source of childhood inspiration, spurred by his father, Frank Weston.

"I was in tune with Africa, and I was always upset about the separation of our people," Weston said. His dad, raised in Jamaica and Panama, cultivated that African consciousness in his only son. He kept literature on Africa and black liberation subjects around their home, and he insisted that Randy know that he is an African living in America.

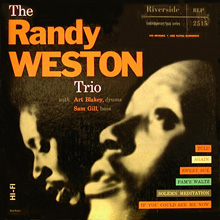

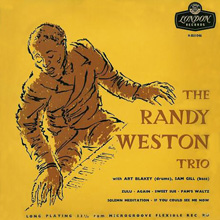

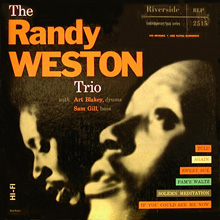

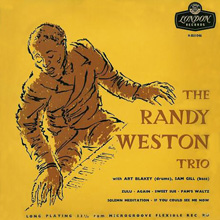

In January 1955, Weston recorded the album Trio (Riverside) with bassist Sam Gill and drummer Blakey, which featured Weston’s first composition "Zulu." Weston’s African sensibilities emerged in his music from the outset, and he got a nod as "New Star" pianist in the 1955 DownBeat Critic’s Poll.

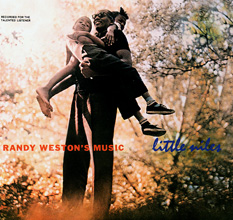

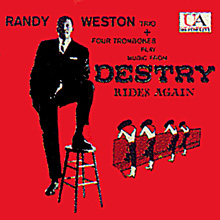

Two different LP cover incarnations of Randy Weston’s Trio record

One evening in 1957, lightening struck when Weston went clubbing. "I first spotted Melba Liston playing trombone with Dizzy Gillespie’s orchestra at Birdland, and when I saw her and heard her play it was instant love," he said. That thunderbolt led to a partnership of Ellington-Strayhorn proportions, lasting until Liston died in 1999.

Melba Liston

Their first collaboration was Little Niles. "After that recording, I was anxious to do an extended piece dedicated to African people," Weston said. "This was an interesting period because everybody was full of fire. The Civil Rights movement was going on."

Weston titled the work Uhuru Afrika, or Freedom Africa [Kiswahili-English translation], in celebration of several new African nations gaining their independence. This provided the suite with historic thrust. Weston engaged Liston to arrange his opus.

In preparation, Weston gathered other vital resources. Earlier in the 50s he had connected with Marshall Stearns in the Berkshires, where Weston worked as a cook at Windsor Mountain resort. At the nearby Music Inn Stearns helmed an unusual series of intellectual programs and history of jazz sessions that struck deep chords in Randy. Weston was struck by Stearns’ African roots approach to jazz history. The historian/educator soon recruited the pianist to act as stylistic demonstrator for his jazz history presentations. Through Stearns’ programs Weston connected with numerous black intellectuals and artists. Among these were Harlem Renaissance writer Langston Hughes, who forged a friendship with Weston, and Nigerian musician Babatunde Olatunji. [Wait for the book for more on this important friendship.]

Langston Hughes

In ’58, as Weston mapped Uhuru Afrika, he sought Hughes’ participation, asking him to write a freedom poem. Hughes’ poem became the invocation. He also asked Hughes to write lyrics for the song "African Lady," the second movement. "Langston’s poem set a tone for the recording session," Weston said. "We were talking about freedom of a continent that has been invaded, its children taken away, the continent of the creation of humanity, and Langston felt it, he knew it."

Weston next sought to translate Hughes freedom poem into an African language with continental commonality. Wondering how this was possible in a continent of more than 900 different dialects, Weston went to the United Nations. "I was anxious to use an African language because I was quite upset by the Tarzan movies and how they depicted Africans," he said. "I spent time at the United Nations and met several African ambassadors and asked them what language I should choose to represent the whole continent; they said Kiswahili."

The 6’7" Weston was quite a vision striding the UN corridors, where he encountered Tuntemeke Sanga of Tanganyika (pre-colonial Tanzania). Weston’s friend Richard Jennings [who sadly passed on to ancestry in late February ’10], a longtime UN administrator, who along with trumpeter Bill Dixon founded the UN Jazz Society, identifie[d] Sanga as a decolonization emissary. "[Sanga] was a petitioner," Jennings said. "During the time of decolonization, different groups and individuals would come in and speak to the [UN] trusteeship counsel on decolonization. [Sanga] was one of those petitioners speaking to why his country should be decolonized."

"Sanga was a professor of Kiswahili, so he translated Hughes’ freedom poem [from English into Kiswahili]," Weston said. "We wanted Brock Peters to do the narration of the opening freedom poem, but Tuntemeke Sanga’s voice was so wonderful, and his Swahili so perfect, that we used him on the recording."

Weston struggled mightily to find a record company willing to record his magnum opus. With These Hands and Jazz a La Bohemia, recorded in March and October 1956 respectively, concluded Weston’s Riverside deal. [Wait for the book for the story of how Randy Weston was the legendary Riverside label’s first modern jazz signing.] He cut Little Niles for United Artists in October ’58.

"I had signed a three-year contract with United Artists, but they weren’t ready for Uhuru Afrika," Weston said. "They said, ‘If you do a popular Broadway show, then we’ll let you do Uhuru,‘ so I went for it."

He settled on the music from Destry Rides Again. Despite Weston’s indifferent attitude toward the music, the results are distinctive, executed by four trombones and his rhythm section. The trombones included Bennie Green, Slide Hampton, Frank Rehak and Liston, who did the arrangements. Weston fondly recalls one of Destry’s savng graces: It was his lone recording with drummer Elvin Jones; with bassist Peck Morrison and percussionist Willie Rodriguez rounding out the personnel.

United Artists balked at recording Uhuru, but Weston found an ally in his label quest: Sarah Vaughan’s husband and manager, C.B. Atkins. [Wait for it… later on in the book Muhammad Ali figures prominently in this relationship.] I didn’t have a bit name, I was just playing trio at the time," Weston said. "I told C.B. Atkins my idea and he went to Roulette Records and talked Morris Levy into it."

In writing the four movements of Uhuru Afrika, Weston beckoned the ancestors. "My cultural memory is of the black church, of going to the calypso dances, dancing to people like the Duke of Iron, of going to the Palladium and hearing the Latin music, and probably going back further to before I was born," Weston recalled. "I collected my spirits, asked for prayers from the ancestors and tried to create what came out of me."

Weston consulted earthly sources for inspiration as well. "I spent time in the Berkshires with the African choreographer Asadata DeFora from Guinea," he said. "He inspired me to collect African traditional music; it was a natural process of listening, but not necessarily listening with your ears, almost like listening with your spirit. When I wrote Uhuru Afrika, it just came out of a magical, supernatural process."

The work is in four movements: "Uhuru Kwanza" signifies African people determining their own destiny. "African Lady" was dedicated to the African woman and all the women who inspired and nurtured Randy along the way, starting with his mom and sister; and "Bantu" signified a coming together of African people. The celebratory final movement, "Kucheza Blues," is for when all of Africa gains its independence, leading to a tremendous global party. Liston wrote the arrangements, but even with all her creative powers, parts were still being copied the day of the recording session. "At my house the day before the recording, guys were writing parts all night long," Weston remembered, with various sheet music tacked to the walls and even the ceiling of his apartment. "The poor copyist’s ankles were completely swollen, we had to carry him down two flights of stairs in a chair, put him in a cab and take him to the studio."

On November 16, 1960, the recording commenced at Bell Sound in Manhattan. Producer Michael Cuscuna, who has twice reissued Uhuru Afrika, described Bell as "a gigantic room," otherwise nondescript, possessing no particular magic. Awaiting those charts was an amazing assemblage of musicians, painstakingly selected. "The key people were Melba’s associates from her big band days, saxophonist-clarinetists Budd Johnson and trombonist Quentin Jackson," Weston said. "When we’d do a big band date, Melba picked the foundation people. We added Gigi Gryce, Sahib Shihab, Cecil Payne, Jerome Richardson, and Yusef Lateef on reeds and flutes; Julius Watkins on French horn; WilliaClark Terry, Benny Bailey, Richard Williams, and Freddie Hubbard on trumpets and flugelhorns; Les Spann on flute and guitar; and Kenny Burrell on guitar.

Melba Liston at the recording session for Uhuru Afrika

Africa is civilization’s heartbeat, so the rhythm section was of utmost consideration. "We wanted a rhythm section that showed how all drums come from the African drum," Weston asserted. "Babatunde Olatunji played African drum and percussion; Candido and Armando Peraza from Cuba expressed the African drum via Cuba; Max Roach played marimba; Charli Persip and G.T. Hogan played jazz drums; and we had two basses, George Duvivier and Ron Carter."

Surviving musicians don’t recall arriving to the session with many preconceived clues about the cultural significance of the session. "Randy had talked about what he was going to do, but basically I had no idea until we got to the studio," Persip said.

Once he arrived and spied the prodigious group of percussionists on the date, Persip’s musical collegiality took over. "I listened to the other drummers, and I played with them. I tried to blend in with them and at the same time play my part, accompanying the ensemble."

"When you hear all those drummers [in the intro], it’s a building process; first is the African thumb piano, the original piano," Weston said. "Then I’m playing the jaw of the donkey percussion instrument. After that comes Armando Peraza on bongos, then Candido, Olatunji, and Charli Persip. And then all the drummers play together."

Ron Carter was a relatively new kid on the block, having hit town the previous year. "Uhuru Afrika was my first awareness that when you go to a date you don’t have any instructions and you should just be prepared for whatever is on the music stand," the bassist said. "It was a surprise to be in the midst of all those guys."

Seeing all those percussionists was rather daunting and called for some different thinking, as Carter calculated his role. "First I noted the pitch of all of those drums. You’ve got congas and bongos, African drums by ‘Tunji… My first concern was if I could find notes to play out of their range, because it takes a hell of a mixing job to get the bass notes out of that mud.

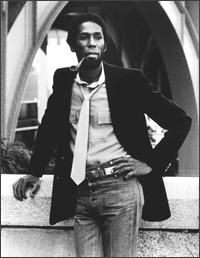

Ron Carter pondered his role on what was one of his earliest recording sessions

"By the same token, respecting and honoring George Duvivier’s presence, I wanted to see what his approach was going to be when those [drummerrs] started banging around. Was it going to be like mine, or different in terms of where to play our parts; when the drums lay out, how do we handle the ranges now that we have the space? It was a real lesson in section bass playing, not having played with another bass player in a jazz ensemble before."

To express Hughes’ lyrics for "African Lady," Weston engaged two beyond jazz singers, baritone Brock Peters and operatic soprano Martha Flowers. Clark Terry recalled Flowers as "a marvelous singer," with whom he and Liston had worked on Quincy Jones’ Free and Easy. Flowers was immediately at ease when she arrived at Bell Sound and spotted Terry and Liston. "When I heard about this music and saw the score, I felt a great sense of dedication to this work. Politically, it made a great musical statement, and that fired me up," Flowers said from her Chapel Hill, NC home. ["African Lady"] wasn’t written in a high key where my voice would sound operatic. It was written in a medium key where my voice had a mellow quality that would lend itself to jazz or music that wasn’t considered classical music."

Weston was thrilled with the date, "because everybody captured the spirit of Africa. Once, we needed a certain kind of

percussion sound and some guys used Coca-Cola bottles. Everybody contributed their ideas because when I record I like to get the musicians’ input. Sometimes they can see or hear things that I can’t hear, so I always like to keep it open. There was a tremendous sense of freedom."

Hughes’ invocation established a reverent tone. "When [the musicians] heard the Langston Hughes poem it was quite dramatic, because that was during the period when Africa was either a place to be ashamed of or feared, you were not supposed to identify with Africa," Weston recalled. "Hearing "Freedom Africa," they knew that freedom for Africa is freedom for us."

Uhuru Afrika was actually recorded and released prior to Weston’s first trip to Africa in 1961, when he was part of a U.S. cultural delegation that included Hughes, Flowers, Olatunji, and others to a festival in Nigeria [see extensive coverage of this historic cultural exchange in African Rhythms]. In 1963, after a second trip to the continent with artist Elton Fax, Weston teamed up with Liston for the Highlife: Music From the New African Nations record (Colpix label). In 1967, he toured throughout Africa on a State Department trip. The last stop on that tour was Morocco, where he eventually settled during 1967-72. [Full details and the ultimate implications of these historic journeys are definitive chapters in Weston’s forthcoming as-told-to autobiography African Rhythms, which will be released in fall 2010 by Duke University Press.]

Uhuru Afrika has been reissued on vinyl and on CD, and in 2006 was part of a Weston Mosaic Select box set [good luck finding that one]. These were labors of love for Cuscuna. "I became a Randy Weston completist, and Uhuru Afrika was the hardest to find as a young collector," Cuscuna said. "I was ecstatic when I finally secured a copy. So much music in the ’60s used Africa superficially as window dressing, but this was the real deal — an honest, well-written, well researched fusion of jazz and African music. When I launched the Roulette reissue serries, I was going to put that one out no matter what."

In 1998, 651Arts presented Uhuru Afrika in Brooklyn, at the Majestic Theater [now the Harvey Theatre at 651 Fulton Street]. Liston and Weston’s music director, T.K. Blue, pieced together the original charts, which were in disarray from Liston’s various relocations and illness. Several of the original musicians, including Clark Terry, Cecil Payne, Candido, and Olatunji, played the reunion. One of the high points of the evening came when Weston wheeled shy Melba — confined to a wheelchair after a 1985 stroke — onstage for kudos.

As underrated as Weston himself, Uhuru Afrika was a landmark undertaking. Yusef Lateef remembrered it as a "discovery and invention in the esthetics of music, because there were decades of knowledge in the studio. I look at it as an amalgamation of abilities that were exchanging ideas and formulating the outcome of that music. A romance of experience happened at that session.

Stay tuned: plans are afoot for a 50th anniversary concert performance of Uhuru Afrika, and you’ll hear it here first in The Independent Ear.